ADVERTISEMENT

A Just Culture for Reporting Medical Errors: Balancing Accountability and Patient Safety

INTRODUCTION

The ability to deliver safe, reliable health care is the goal of all health care systems. To build a culture of safety, clinicians should feel confident discussing medical errors openly and honestly to identify learning opportunities to correct areas of weakness within a system. However, many errors go unreported by health care workers, which can potentially result in further harm and risk patient safety if mistakes are not addressed and resolved.1

Error reporting is often complicated by how errors are defined, what information is reported, and who is required to report.1 Most states have mandatory event reporting systems, although policies may vary.2 Some states mandate that hospitals report only incidents causing serious harm, while others include “near misses” (i.e., errors caught before reaching the patient or do not cause injury or harm upon reaching the patient).2 In addition, error reporting may be timely and take away from other duties of a busy clinician, resulting in an incomplete account of the incident.

Despite these procedural issues, the major reason clinicians fail to report errors is that self-reporting will result in repercussion.2 Employees keep quiet for fear of being punished or fired, which makes it more likely that the same mistakes will be repeated. This type of punitive culture instills fear, discourages reporting, and prohibits the learning and improvement required to reduce medical errors.

The transition to a blame-free culture in the medical field occurred in the mid-1990s with the acknowledgement that humans make mistakes and no practice is without error.1 Focus began to shift from the individual to the system processes that contributed to errors.1 While this blame-free culture did not discipline employees for honest mistakes, it failed to discipline those who exhibited repeated errors or participated in negligent or careless behavior.

The ideal safety system aims to strike the balance between blame-free and discipline while holding individuals accountable for their behavior. This objective serves as the premise of a Just Culture. When evaluating the benefits of punishment versus learning, organizations should ask themselves a few key questions. To prevent errors, is it better to punish everyone who makes a mistake or is it more beneficial to learn from errors being reported openly and communicated back to staff?3 Does the threat of disciplinary measures increase a person’s awareness of risks? 3 Does providing safety information and knowledge outweigh learning through punishment?3

NATURE OF HUMAN ERROR

A Just Culture requires a focus shift from errors and outcomes to system design and human interaction, and it requires management of employees’ behavioral choices.4 There are numerous reasons humans make behavioral choices in circumstances where an error occurs. Consider the following scenarios:

- Two pharmacy technicians pick the wrong drug to fill the medication cart. One technician realizes her mistake, but the other technician fills the medication drawer with the incorrect medication. Later, the patient receives the incorrect medication and has an adverse reaction. After review of the incident, it is discovered that 2 look-alike drugs were stored next to each other on the same shelf.

- A pharmacy technician is asked to review medications to ensure that no stock is out-of-date. The pharmacy technician forgets, but due to fear of her supervisor’s reaction, she reports that she performed the task.

- A pharmacy technician delivers the wrong intravenous medication to the floor. The nurse catches the error and returns the medication to the pharmacy. Since no adverse event occurred, the pharmacy team decides not to investigate the error.

In a Just Culture, which focuses on value and shared accountability, individuals should address all errors and near-miss situations whether they harm patients or not. However, if mistakes occur due to a faulty system of which the employee has no control, this should be viewed as an opportunity to improve the system rather than hold that employee accountable.

In the first scenario, even though human error was involved, the organization needs to reevaluate its storage system to ensure that look-alike drugs are not stored next to each other. In the second scenario, the employer must address the dishonest behavior of the pharmacy technician. Honest disclosure without fear of reprimand is critical in a Just Culture.4 In the third scenario, the employer should investigate the error even if the medication did not manage to reach the patient. An investigation may uncover latent errors (i.e., errors that have not yet manifested) in the system.

There are 3 different classifications of behavior including human error, at-risk behavior, and reckless behavior.4 When considering the nature of human errors, it is necessary to consider the notion of intent.4 Human error includes both slips and lapses, neither of which have the intent to cause harm. Slips are actions that were not carried out as intended or planned.4 The task is something people do all the time successfully but for some reason they err. An example of a slip would be if a pharmacy technician forgets to put an ingredient back into the refrigerator after using it to compound even though they repeat this task daily after each use of the ingredient. This may happen if the technician is briefly interrupted and forgets to come back to the task. Lapses are missed actions or omissions where the perpetrator is often conscious of the action and believes it will not cause harm.4 Mistakes involve errors due to improper planning or faulty intention, but the individual still believes the action to be correct.4 At-risk behavior includes both intention and the violation of rules and is considered to be a conscious drift from safe behavior.4 With reckless behavior, individuals are consciously aware of their behavior and its associated risks.4

In a Just Culture, individuals should address each type of behavior and actions taken should, in part, be based on the intent of the behavior. Omissions, slips, lapses, and mistakes fall under the category of honest mistakes (i.e., not deliberate) while negligence and criminal actions are considered deliberate acts.3 Organizations must investigate each error to determine what category it falls into and the extent to which blame should be attributed to the individual(s) or to the system.3 It is unacceptable to punish all errors regardless of their origin and circumstances, and it is also unacceptable to give blanket immunity to all personnel that contribute to errors. A Just Culture strives to find the balance between acceptable and unacceptable behavior and determine in which situations reprimand is appropriate.3

There are multiple reasons why individuals are reluctant to report errors, including3

- Innate human reaction to making mistakes does not usually lead to confessions

- Potential reporters cannot always see the added value of making reports

- Trust problems exist with management

- Fear of punishment

- No incentives are provided to encourage voluntarily reporting

- Extra work related to error reporting is not usually desirable

- There is a natural desire to forget that the occurrence ever happened

A study in 2020 evaluated data from a 2016 survey performed among hospital pharmacists. Researchers aimed to identify error reporting frequency and examine the association between error reporting and work environment perceptions, specifically pharmacists' perceptions of management to promote patient safety, teamwork, and staffing issues.5 The data showed that 32% of pharmacists reported an error if the error could have harmed the patient. Additionally, 17.6% of pharmacists reported an error if it had no potential to harm the patient, and 12.3% of pharmacists reported an error if it was corrected before reaching the patient.5 The researchers also concluded that pharmacists' positive perceptions of their work environment's patient safety culture was associated with higher frequencies of near-miss event reporting.5

The data from the 2016 survey agrees with other studies which have demonstrated that pharmacists who perceive high levels of communication openness at their institution were more likely to submit error reports and those who did not feel there was adequate feedback or sufficient preventive procedures were less likely to report errors.6,7 Based on these studies, it is evident that positive perceptions of managerial response to error reporting and the departmental culture related to promoting patient safety contribute to increased error reporting.

DEFINING A JUST CULTURE

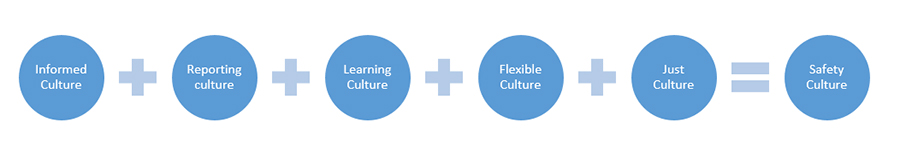

A safety culture involves many structural components related to both the individual and the organization. Figure 1 indicates the necessary components that make up a culture of safety.

Figure 1. The Components of a Safety Culture3

In an informed culture, management has current knowledge about the human, technical, organizational, and environmental factors that determine the system’s safety.3 In a reporting culture, individuals are prepared to report their errors and near-misses.3 Practicing in a learning culture signifies that an organization possesses the willingness and the competence to make changes based on its safety information analysis.3 In a flexible culture, the organization is able to reconfigure processes to maximize patient safety.3 A Just Culture is defined by an atmosphere of trust in which individuals are not punished for actions, omissions, or decisions which correspond with their experience and training. A Just Culture, however, does not tolerate gross negligence, willful violations, or destructive acts.3 An organization that strives for value-driven care and safe patient outcomes will have all of these ideals in place, creating a safety culture.

Prerequisites for a Just Culture

Certain elements are required for the success of a Just Culture climate, whether error reporting is mandatory or voluntary. These elements should be in place to facilitate the quantity and quality of error reporting and to increase trust between management and employees. There should also be a clear distinction between acceptable and unacceptable behavior. Organizations should uphold the following factors in a Just Culture3:

- Protection against disciplinary proceedings as far as it is practicable and legally acceptable

- De-identified error reports when possible to promote confidentiality and assure employees that obtaining feedback on organizational factors leading to errors is much more valuable than blaming

- Separation of the department collecting and analyzing the reports from those with the authority to institute disciplinary proceedings

- An easy-to-use error reporting system so employees do not perceive the reporting process as an extra, labor-intensive task

- Prompt acknowledgement of error reports and communication of actions to be taken and an anticipated timeline

- Provision of feedback for each error and a subsequent plan to prevent similar errors in the future

- A solid foundation of trust between management and employees

Benefits of a Just Culture

In addition to increased reporting and corrective actions taken, creating and upholding a Just Culture comes with other benefits. Establishing the standards for acceptable versus unacceptable behavior fosters communication between numerous departments across institutions that may not otherwise interact. This increase in open and honest communication along with an agreement as to where the lines of punishment are drawn helps cultivate an environment of trust.3

Operating within a Just Culture helps clarify job expectations, establishes guidelines for behaviors that deviate from policies and procedures, and promotes continual review of those policies and procedures. This ultimately leads to a safer system. The organization will not only be more efficient from a safety perspective but often times the errors that cause safety issues lead to decreased productivity and profit loss.3 Thus, a Just Culture can also have a positive economic influence on an organization.

ESTABLISHING A JUST CULTURE

Several factors influence health care professionals’ sense of what constitutes a fair (or just) incident reporting process. Employees perceive greater justice if the likelihood of disciplinary action depends on the level of perceived responsibility or guilt and the severity of that disciplinary action seems proportional to the error’s seriousness.8 Employees also perceive greater justice if disciplinary actions are consistent with established organizational policies where disciplinary consequences are defined for particular errors.8 In addition, employees value a standardized procedure which permits some control over the outcome and identifies their own individual value in relation to the organization.8

Various procedural rules related to the error reporting process should be in place8:

- Allowing individuals to voice their own views during the investigation process

- Allowing individuals to have some influence on the actual outcome

- Applying the process consistently across people and time

- Ensuring decision makers are neutral

- Ensuring all information obtained is accurate

- Establishing appeal procedures for all employees

- Allowing all groups affected by the decision to be heard from

- Upholding personal standards of ethics and morality during the process

Steps to Implement a Just Culture

Organizations that wish to establish a Just Culture should follow 7 major steps3:

- Reduce the Legal Deterrents: Organizations should protect employees filing error reports against a disciplinary proceeding (if feasible) and establish a legal framework that supports reporting and investigating errors in the context of a non-punitive environment.

- Develop Reporting Policies and Procedures: Policies and procedures should establish the necessity of confidentiality in the reporting process, separate the investigating agents from those who have authority to institute disciplinary proceedings and impose sanctions, and illustrate the organization’s commitment to safety.

- Establish Reporting Methods and Assessment: The ease with which an employee reports an error should take priority. Organizations should provide clear directions to file a report and easy access to the reporting mechanism. An organization should decide if the reporting system is to be mandatory or voluntary and whether it should be anonymous, confidential, or an open reporting system. Ideally, an organization should institute a mixture of reporting methods since 1 method may not suit everyone’s needs. It may be helpful to survey the needs of potential users to better understand which reporting method would be readily accepted. Organizations should determine which reports will be investigated (e.g., the most serious adverse events, those with the greatest learning potential), what that investigative process will look like (e.g., face-to-face interviews, on-site investigations), and who will perform investigations. Organizations should clearly define a process for determining fault so it can be understood and accepted by all employees.

- Determine the Players: Several people will need to be involved in implementing and maintaining the system. Organizations must appoint a champion of the system to guarantee that confidentiality is preserved despite external or managerial pressures. They should decide who will educate users, collect and analyze the data, provide feedback, and coordinate disciplinary action. It may be challenging to have the appropriate finances and people to implement and maintain the system.

- Develop the Reporting Form: Once an organization decides what the error reporting information is to be used for, it is easier to determine the type of information that the system should collect. Some organizations may choose to present case studies, while others may only wish to present summaries as a manner of feedback. Determining how the information will be captured (e.g., electronically, paper, or both) also helps to identify reporting system requirements. Capturing too much or irrelevant data will place a burden on the reporting party, therefore organizations must strike a balance between what information is valuable and in just the right amount to be useful to error analysis.

- Develop a Template for Feedback: Organizations should consider what type of information needs be disseminated (e.g., summaries, human factors data, case studies, recurring errors). They must also determine how they will provide the feedback (e.g., website, newsletter), how often they will provide it, and who is responsible for providing that feedback.

- Develop an Education and Implementation Plan: Organizations need to explain to employees how the new system fits into an existing system and any changes that occur in the legal system as a result of new policies. They should also train a champion (individual or team) to encourage other employees to utilize the system. Organizations can consider having a special week to implement the system using email and internet to announce all activities related to training and implementation dates. They can also design posters to help learners get visualize the steps required for reporting purposes, which may help ease the training process.

Maintaining the Culture

Employees must feel motivated to continue to report medical errors. Organizations must maintain the open and trusting culture and continually investigate new ways to motivate employees. The following are a few ideas to help with this initiative3:

- Publicize participation rates in different areas of the organization to show individuals that their colleagues value the system

- Ensure the system maintains employees’ views and is not used to support existing management priorities

- Focus on the positive consequences of reporting errors

- Involve management in the reporting process to show commitment to the system

- Ensure employees’ voices are continually involved in decision-making and problem-solving processes

- Develop positive reinforcement for reporting errors so employees feel their actions positively benefit safety

- Show evidence of how safety can enhance production, efficiency, communication, and cost benefits within the organization

EVALUATING ERRORS

Researchers have developed many tools to identify, analyze, and prevent errors. Methods used to address errors include performing a root cause analysis, using the human factors approach, and applying the Just Culture Tool developed by the National Patient Safety Foundation.

Root Cause Analysis

A root cause analysis (RCA) investigates events surrounding a medical error to eliminate the possibility or reduce the likelihood of a future similar event. The investigation focuses on a broader understanding of the error with less focus on individual culpability and more on organizational and wider system factors.9 The term itself only indicates an analysis when in fact the wider purpose is to implement action steps to prevent similar errors in the future. For this reason, the National Patient Safety Foundation introduced a more accurate term to describe this investigative process, the Root Cause Analysis and Action (RCA2).10

The steps to perform an RCA2 are as follows10:

- Graphically describe the event using a chronological flow diagram

- Identify gaps in knowledge surrounding the event

- Visit the location of the event to obtain firsthand knowledge about the workspace and environment

- Evaluate equipment or products that were involved

- Conduct interviews of involved parties including staff, affected patients, and their families or caregivers

- Identify internal documents (e.g., policies, procedures, medical records, maintenance records), external documents, and/or recommended practices to review

- If necessary, identify appropriate expertise to understand the event

- Enhance the flow diagram to reflect the final understanding of events and where hazards or system vulnerabilities are located

- Provide feedback to the involved staff, patients, and organization as a whole

- A member of management should ensure implementation of the RCA2 recommendations, measurement of actions, outcomes, and feedback

Despite the intent to look at the wider system, literature has criticized RCA use. Health care is a complex system, so in most cases, there are many contributing factors to a medical error. Critics suggest that an RCA studies components in isolation and does not appreciate the importance of their interactions with other components.9 Research shows that despite an RCA the same events may reoccur multiple times, suggesting that a RCA is an ineffective tool to prevent errors.9

Another concern is that RCAs rarely consider design-related factors and instead solutions are focused on behavioral interventions (e.g., training, policy reinforcement), which may not be most effective in eliminating the problem.9 For this reason, focus has been moving towards investigating how people and systems interact to affect safety.

Human Factors Approach

The science of human factors focuses on designing systems that are resilient to unanticipated events by supporting work systems that promote human performance while maximizing optimal and safe patient care.11 Investigations include gathering data on human physical and cognitive characteristics and their interactions with the overall system.11 This may include11

- designing workstations for optimal work flow

- developing products that are useful, safe, reliable and desirable to improve job performance

- comparing usability between different software programs

- researching human cognition and decision making to influence system design and training programs

Human factors science addresses problems by modifying the system design versus modifying human behavior. Most frequently this involves changing technologies, processes, tools, and other inanimate work system components.11

Just Culture Error Analysis

When acting within the framework of a Just Culture, it can be difficult to distinguish between those who make a conscious decision to complete an unsafe action despite knowing it is unsafe and those who experience a slip, lapse, or honest mistake without intent to cause harm. The National Patient Safety Foundation published a Just Culture Tool that institutions can use to evaluate errors without bias or judgment.12 No perfect algorithm exists for reviewing a medical error to determining an employee’s culpability (i.e., responsibility for a fault or incorrect action). The Just Culture Tool considers the individual’s intent and compares their actions to that of a competent employee with similar training.12 When using this tool, it is important to also evaluate if system errors exist which may also have impacted the medical error.

Using the Just Culture Tool

Regardless of patient outcome, if an investigation determines that the associate involved met the standard of care, then the error is considered a blameless event.12 In this case the organizations should console the associate (i.e., accept that the error has occurred and identify any system improvements to prevent future errors).12 For example, if a pharmacist filled a prescription for amoxicillin and the child later had an anaphylactic reaction, the organization should investigate the error. If this investigation shows that the child had never been previously exposed to the drug and had no known allergies, the organization cannot hold the pharmacist accountable for the adverse event and they should console this employee.

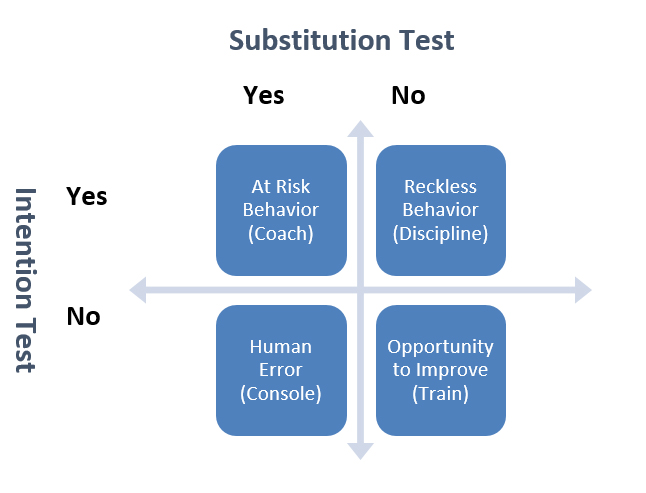

When the involved employee does not meet the standard of care, the organization should perform the test of intention and the substitution test to help further clarify the event. After investigating the error, the test of intention determines if the act of not following best practice was intentional.12 In other words, did the person knowingly violate the standard of care? The substitution test determines if other competent colleagues with an equivalent level of training would have done the same thing if faced with the same situation and set of circumstances.12 If other competent colleagues would have made the same decision and completed the same actions, then blaming the individual is not likely appropriate as there is evidence that the issue has a larger scope. Figure 2 outlines the steps for instituting the Just Culture Tool in situations where employees do not meet the standard of care.

Figure 2. Behavioral Outcomes in a Just Culture12

The results of the substitution test and the intention test categorize the action into 1 of the 4 quadrants in the figure. Which quadrant the behavior falls into determines the recommendation for further action. To better understand how to utilize this figure, consider an example from each quadrant:

- Human error (not intentional, a colleague could have done the same): A pharmacist picks hydralazine instead of the ordered hydroxyzine on the filling screen. The patient experiences severe hypotension (low blood pressure) and falls, leading to a fracture. The pharmacist made the error largely because the 2 medications that sound and look alike are near each other on the order screen. In this situation, the organization should console the pharmacist and acknowledge that there is a bigger system related problem with the placement of the medications in the ordering process.

- At-risk behavior (intentional, a colleague could have done the same): To save time, a pharmacy technician draws up numerous syringes with different medications and makes different solutions with each. In the process, the labels are almost mixed up, but the pharmacist catches the error. The technician demonstrated risky behavior and the organization should coach them about the reason for the process as designed request that they commit to better choices.

- Opportunity for improvement (not intentional, a colleague would not have done the same): A technician misreads the directions on the prescription and types 4 times daily (QID) instead of once daily (QD). The organization should question the competency of the technician, and there is likely an opportunity for training.

- Reckless behavior (intentional, a colleague would not have done the same): A pharmacy technician preparing chemotherapy did not use proper protective equipment because it was in the back in the storage room and not in the sterile compounding room. Restocking supplies would have taken too much time, and the technician was in a hurry to finish her shift. As a result, the chemotherapy was contaminated and when the nurse administered the drug to the patient they had a severe skin reaction. The pharmacy technician acted recklessly and should be disciplined.

If it is apparent that an employee demonstrates impaired practices either through substance abuse or a health issue or has intentionally harmed a patient, then the organization should immediately escalate the incident to the appropriate disciplinary party (e.g., human resources, legal affairs). Table 1 demonstrates examples of medical errors and disciplinary actions that are recommended in a Just Culture.

| Table 1. Errors and Recommended Responses in a Just Culture4 |

| Category |

Definition |

Recommended Response |

| Impaired judgment |

Cognition was impaired by illegal substances, cognitive impairment, or severe psychosocial stressors |

Discipline is warranted; consider temporary work suspension (especially if illegal substances were involved); determine if employee needs medical intervention and offer help where appropriate |

| Malicious action |

Harm was intentional |

Discipline and/or legal proceedings are warranted; suspend employee from duties immediately |

| Reckless action |

Consciously violated a rule and/or made a dangerous or unsafe decision with little or no concern of risks involved |

Discipline may be warranted; employee may need re-training; employee should participate in teaching others the lessons learned |

| Risky action |

Made an unsafe choice; faulty or self-serving decision-making may be involved |

Coach the employee; employee should participate in teaching others the lessons learned |

| Unintentional error |

An error is made while working appropriately and in the best interests of the patient |

Employee is not accountable for the error; employee should participate in the investigation and teach others about the results |

| Repeated mistakes |

Employee continually makes same/similar mistakes |

Consider that the employee is in the wrong position; evaluation is warranted; consider coaching, transfer or termination |

CASE STUDY

Scenario: A pharmacy technician is waiting on patients at the pharmacy counter. A patient approaches the counter and the pharmacy technician asks the patient for her name. The patient states, “Mrs. Isaacson.” The pharmacy technician locates the customer bag with the last name of Isaacson and rings out the prescription while asking the customer if she has any questions for the pharmacist. The patient indicates she does not wish to speak to the pharmacist, takes her prescription, and leaves the pharmacy never looking inside the bag. Later that evening when she prepares to take the medication, she notices it is not the correct medication and it was for another person with the last name Isaacson. She promptly returns the incorrect medication to the pharmacy without having taken any doses.

The pharmacy technician did not ask for a first name, street address, or birth date, which all would have verified that the wrong patient’s medication had been retrieved. In fact, it is company policy to verify the address with every prescription. The pharmacy manager has noticed on several occasions that this technician failed to verify the address, especially when the pharmacy was busy. Each time, the manager reminded the technician that it was against company policy to dispense medication without verifying the patient’s address. The technician continually made excuses that she did not want the customer line to get backed up by taking extra steps during especially busy times in the pharmacy, but each time she promised not to repeat the action.

Analysis: Since the pharmacy technician did not meet the standard of care, the employer should perform the test of intention and the substitution test to help further clarify the event. According to the Just Culture Tool, this situation falls under the reckless behavior category (i.e., intentional and a colleague would not have done the same) and discipline is recommended. However, this scenario warrants further considerations. The pharmacy manager has counseled the technician on various occasions that it was required to verify a patient’s address before dispensing medication. Due to repeated mistakes, the manager should consider if this pharmacy technician is in the wrong position and consider an appropriate disciplinary action, suspension, or termination.

CONCLUSION

Despite an expectation of perfection, it is well-known that to err is human. Many health care workers are afraid to report errors for fear of retribution. In a punitive environment, remaining silent about a medical error may result in further patient harm if the system causing the mistake is not identified and corrected. A Just Culture, as opposed to a culture of blame, changes how an organization perceives and acts upon errors. This type of culture treats errors as system failures rather than personal failures with the belief that designing a better system can eliminate some, if not most, errors.

The framework of the Just Culture ensures a balanced accountability for both employees and the organization responsible for designing and improving systems in the workplace. In a Just Culture, the individuals are not accountable for errors, but they are responsible for their behavioral choices. Establishing a Just Culture requires that organizations build awareness of the benefits of reporting medical errors as a learning tool, implement policies that support the culture, and maintain the critical foundation of trust between management and employees. By empowering employees to proactively monitor their work environment and participate in medical error reporting an organization will more effectively promote patient safety by continually learning, adjusting, and redesigning systems for optimal patient care.

REFERENCES

- Rogers E, Griffin E, Carnie W, et al. A just culture approach to managing medication errors. Hosp Pharm. 2017;52(4):308-315. doi:10.1310/hpj5204-308

- Weissman JS, Annas CL, Epstein AM, et al. Error reporting and disclosure systems: views from hospital leaders. JAMA.2005;293(11):1359–1366. doi:10.1001/jama.293.11.1359

- European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation. Establishment of “Just Culture” principles in ATM safety data reporting and assessment. March 31, 2006. Accessed September 14, 2021. https://www.skybrary.aero/bookshelf/books/235.pdf

- Boysen PG 2nd. Just culture: a foundation for balanced accountability and patient safety. Ochsner J. 2013;13(3):400-406.

- Noureldin M, Noureldin MA. Reporting frequency of three near-miss error types among hospital pharmacists and associations with hospital pharmacists' perceptions of their work environment. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(2):381-387. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.008

- Patterson ME, Pace HA, Finchman JE. Associations between communication climate and the frequency of medical error reporting among pharmacists within an inpatient setting. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):129-133. doi:10.1097/PTS.0b013e318281edcb

- Patterson ME, Pace HA. A cross-sectional analysis investigating organizational factors that influence near-miss error reporting among hospital pharmacists. J Patient Saf. 2016;12(2):114-117. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000125

- Weiner BJ, Hobgood C, Lewis MA. The meaning of justice in safety incident reporting. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(2):403-413. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.08.013

- Sampson P, Back J, Drage S. Systems-based models for investigating patient safety incidents. BJA Educ. 2021;21(8):307-313. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2021.03.004

- National Patient Safety Foundation. RCA2 improving root cause analysis and actions to prevent harm. June 16, 2015. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/endorsed-documents/endorsed-documents-improving-root-cause-analyses-actions-prevent-harm.ashx

- Russ AL, Fairbanks RJ, Karsh BT, et al. The science of human factors: separating fact from fiction. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(10):802-808. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001450

- National Patient Safety Foundation. A Just Culture Tool. September 22, 2016. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://zdoggmd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Just-Culture-Tool_NPSF-Version_Adelman_9_22_16.pdf

Back to Top