Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

The Week in Review-COVID-19: June 5, 2020

INTRODUCTION

As the number of American deaths from COVID-19 passed the 100,000 threshold, the outlines of life during the summer and fall of 2020 were becoming clearer: Much variation in activities among states and even from county to county, lots of decisions for parents of young children to make about education, much stress for physically distant residents in long-term care facilities, profound levels of unemployment and economic stress, and some reason for hope for effective therapeutic agents and preventive vaccines.

During the last week of May, the projected number of COVID-19 deaths by August 4 was lowered by 11,000 to 132,000 by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. Whether this model adequately accounts for the relaxing of physical distancing orders remains to be seen, but the number of hot spots producing local morbidity, mortality, and stress on the health care system is concerning. News reports describe limited or no intensive-care unit beds available in Montgomery, Alabama, the Twin Cities area of Minnesota (where social unrest has the potential to accelerate viral spread), Omaha, Nebraska, and the entire state of Rhode Island.

A very positive outcome of the pandemic is the impressive level of cooperation evident among medical researchers, biopharma companies, and governmental and nongovernmental funding sources around the world. Such collaborations will hopefully have a long-term impact on the way medical research is conducted, and the agencies responsible for product-approval decisions may need to meet new expectations regarding their processes and timelines.

THE VACCINE SCENE

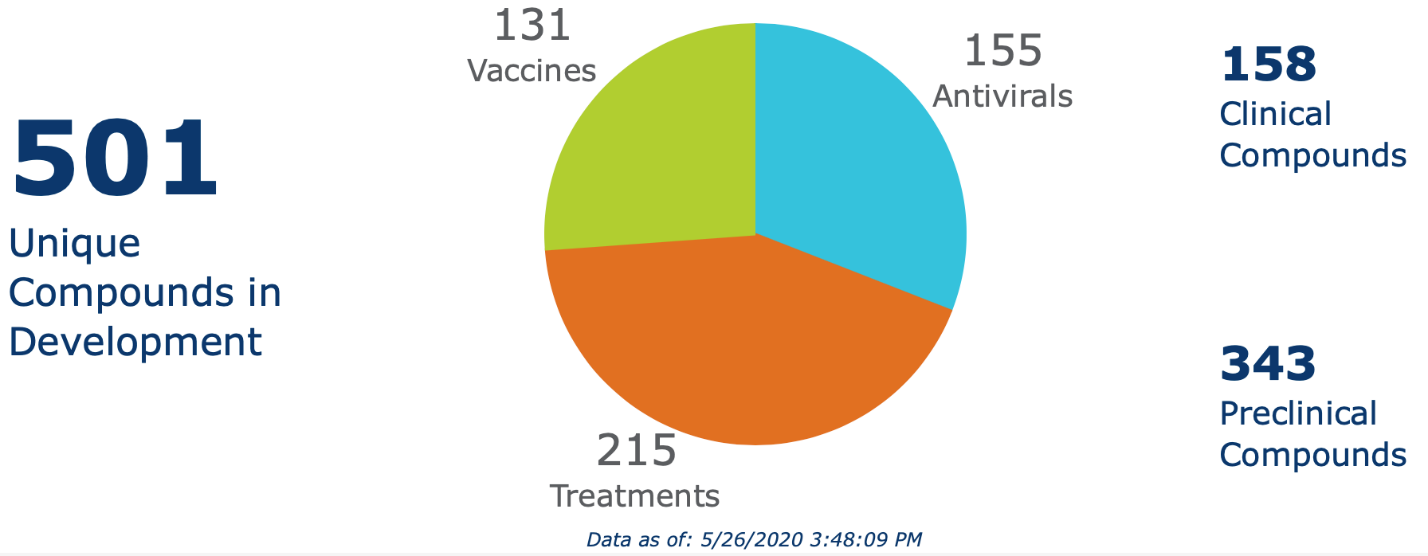

More than 500 therapeutic or vaccine candidates targeting the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are in development, according to a tracker maintained by the biotechnology industry organization BIO (Figure 1). When this program was prepared in late May, the candidates included 155 antiviral agents, 215 immunologic and other treatments, and 131 vaccines.

Figure 1. The COVID-19 Therapeutic Development Tracker

Source: BIO. Available at: https://www.bio.org/policy/human-health/vaccines-biodefense/coronavirus/pipeline-tracker.

Accessed on: May 27, 2020.

Authors of a Clinical Implications of Basic Research article on the scope and speed of COVID-19 research in the New England Journal of Medicine described a “surreal, accelerated world” in which “advances are quickly out of date.” They continued: “Many new experimental three-dimensional structures of the S protein and other viral targets are being reported in quick succession, a process that requires the simulations and docking to be refined and repeated. Artificial intelligence is being used to predict drug binding. Different types of experimental laboratory screening programs have been set up all over the world and are ramping up. Meanwhile, for several SARS-CoV-2 proteins, the virtual high-throughput screening and ensemble docking pipeline is in full production mode, both on supercomputers and with the use of vast cloud-computing resources. None of this guarantees success within any given time frame, but a combination of rationality, scientific insight, and ingenuity with the most powerful tools available will give us our best shot.” [Parks & Smith, 2020]

That scenario is certainly true for the vaccines in development. A public–private biomedical research partnership led by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV), has established 4 working groups “to support a prioritization of therapeutic and vaccine candidates, no matter who has developed them,” NIH director Francis S. Collins wrote with coauthors in a JAMA Viewpoint. The Preclinical, Therapeutics Clinical, Clinical Trial Capacity, and Vaccines Working Groups each have 2 cochairs, one from NIH and one from industry. [Collins & Stoffels, 2020]

Vaccine candidates include both repurposed products — the bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine in particular — but most are new vaccines developed based on either older platforms or newer technologies such as mRNA, DNA, cellular, and protein vectors. BIO maintains a table of the most advanced COVID-19 vaccine candidates. These include the BCG vaccine (Merck, Pasteur Institute, and other sponsors) that is now in phase 3 clinical trials, mRNA-1273 (Moderna) that recently completed phase 1/2 trials, and a recombinant adenovirus type-5 (Ad5) vectored COVID-19 vaccine (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) being developed by the University of Oxford in a consortium with AstraZeneca and other partners that is beginning phase 2/3 clinical testing.

Phase 1 testing showed that the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine was safe, producing no severe adverse reactions. The most common injection site adverse reaction was pain, occurring in 54% of 108 participants in the dose-escalation, open-label trial conducted in Wuhan, China, followed by fever (46%), fatigue (44%), headache (39%), and muscle pain (17%). Participants had neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 by day 14 of the trial, and this continually increased during the 28-day test period. [Zhu et al., 2020]

How vaccine testing and approval will play out against viral spread and associated morbidity and mortality is unknown, and the timeline for this process has been fodder for endless discussions by cable news pundits. If the vaccines work and receive emergency use authorization for use in the United States, millions of doses could be available quickly as the major vaccine manufacturers are planning to begin production while trials are in progress.

In that case, pharmacies would likely be involved in the race to vaccinate as many people as possible as fast as possible. As valued members of the immunization community, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians will be important advocates of COVID-19 vaccination. This advocacy will be needed to achieve the 55% to 82% vaccination rates needed for herd immunity to stop spread of the highly contagious SARS-CoV-2, authors of a recent op-ed article in JAMA noted. [DeRoo et al., 2020] They suggested these public health messages in preparing Americans for a future COVID-19 vaccine:

- As soon as a COVID-19 vaccine is shown to be safe and effective, it should be delivered and distributed equitably to those at highest risk for complications and disease transmission.

- Before the vaccine is available, an educational program should be designed to address obstacles to vaccine acceptance and launched using linguistically and culturally competent messages.

- This robust educational campaign should include traditional and social media and focus in particular on social influencers and sources of misinformation.

- Vaccine advocates, including frontline health care workers, should be trained to provide strong recommendations for COVID-19 vaccination. Messaging should include their personal experiences with COVID-19 and the vaccine when relevant.

COVID-19 ASSAYS: PHARMACY’S ROLE, TECHNICAL CHALLENGES

The need for widespread testing of the populace in the United States provides an opportunity for community pharmacies to expand their already-sizable role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Setting up and staffing this service could expand the public’s view of the pharmacy as a health care center, establish a new revenue stream, and prepare staff for the possibility of conducting large-scale COVID-19 vaccine administration when products become available.

For those in community pharmacies who are considering testing services, the following are good sources of information about the legal and reimbursement details, types of assays available and how they work, and the recognized problems with COVID-19 assays:

Two types of COVID-19 tests are available. Products that assay for viral antigens or molecular targets such as nucleic acids analyze material obtained through nasopharyngeal swabs to identify people with active infections of SARS-CoV-2. Serology tests use small amounts of blood to test for antibodies to the virus, identifying people previously exposed and who may some degree of immunity.

Given the continued limited number of available antigen and nucleic acid tests, CDC designated these priority groups:

- Hospitalized patients with symptoms

- Healthcare facility workers, workers in congregate living settings, and first responders with symptoms

- Residents in long-term care facilities or other congregate living settings, including prisons and shelters, with symptoms

The CDC said priority should be given to

- Persons with symptoms of potential COVID-19 infection, including fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, muscle pain, new loss of taste or smell, vomiting or diarrhea, and/or sore throat.

- Persons without symptoms who are prioritized by health departments or clinicians, for any reason, including but not limited to: public health monitoring, sentinel surveillance, or screening of other asymptomatic individuals according to state and local plans.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has authorized pharmacists to order and administer COVID-19 testing, including serology assays, based on its interpretation of the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness (PREP) Act. This opinion, while not legally binding, means that the PREP Act overrides state and local regulations that might limit pharmacy’s role, according to NCPA, empowering them to offer the covered services.

To offer testing services of any kind (including COVID-19 and other tests), pharmacies must be registered as a nonresearch laboratory under regulations governed by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA). CLIA recognizes laboratories conducting tests of varying complexity. Point-of-care (POC) tests used in pharmacies generally are in the “waived” category based on their simplicity and low risk for error. Thus, community pharmacies must obtain a Certificate of Waiver, usually through the state board of health, to conduct such tests, according to the Bula Intelligence website.

The next important step in offering testing services is to get paid. Some patients are willing to pay out of pocket for testing, but coverage through carriers greatly expands those interested in these services. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has issued an Medicare Learning Network Matters article on how Medicare pharmacies and other suppliers can enroll temporarily as independent clinical diagnostic laboratories during the COVID-19 public health emergency. NCPA, in an online video interview with Mary Stoner of Electronic Billing Services, provides excellent practical advice and details on working through the CMS process of becoming recognized as a CLIA-waived, reimbursement-eligible entity under Medicare Part B. The application is temporarily free and establishing these reimbursement numbers could be expanded into durable medical equipment, Stoner advised.

While POC tests are simple and low risk, errors and mishaps can happen. Incorrect results give people a false sense of security or cause anxiety and worry. Employees can be exposed to potentially hazardous materials, and liability is a concern. Pharmacy owners and managers should check with their liability insurance carrier on whether these activities are or can be covered or obtain legal advice on this aspect of COVID-19 testing.

Antigen tests are used for detecting active viral infections. Antigenic POC tests that are CLIA-waived are generally rapid immunoassay tests that can quickly report the detection or absence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein antigen, according to the American College of Physicians. Problems with accuracy, particularly false-negative results, have been reported with these tests, including the highly publicized Abbott NOW POC test.

Immunoassay tests are performed on nasopharyngeal or nasal swab specimens. Detailed guidance for safely obtaining these samples is available in a video on the New England Journal of Medicine website. It includes information on preparation and equipment, procedures, handling the specimen, and removing personal protective equipment.

More sensitive and specific antigenic tests use real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) assays for SARS-CoV-2. rRT-PCR assays have greater specificity and sensitivity than immunoassays. These tests have greater complexity and are not CLIA-waived.

As shelter-in-place orders have been lifted, states have implemented more aggressive programs of antibody testing. These are important – even critical — for understanding how many people have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, including asymptomatic individuals; identifying those likely protected against the virus and therefore do not need to restrict activities; and understanding more about the scale and future direction of the pandemic.

Serologic tests use small blood samples to identify antibodies to viral surface proteins. A positive test indicates past viral exposure, not current infections. In interim guidelines updated on May 23, the CDC provided guidance on antibody testing. The agency summarized its key points as follows:

- Serologic assays for SARS-CoV-2 now have Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has independently reviewed their performance.

- Currently, there is no identified advantage of assays whether they test for IgG, IgM and IgG, or total antibody.

- It is important to minimize false-positive test results by choosing an assay with high specificity and by testing populations and individuals with an elevated likelihood of previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Alternatively, an orthogonal testing algorithm (i.e., employing two independent tests in sequence when the first test yields a positive result) can be used when the expected positive predictive value of a single test is low.

- Antibodies most commonly become detectable 1 to 3 weeks after symptom onset, at which time evidence suggests that infectiousness likely is greatly decreased and that some degree of immunity from future infection has developed. However, additional data are needed before modifying public health recommendations based on serologic test results, including decisions on discontinuing physical distancing and using personal protective equipment.

Opportunities for pharmacists to become involved in antibody testing are developing, but the supply of these test kits are limited (as are those for antigen testing). Watch the NCPA website for more information as this situation improves.

Pharmacists’ Roles in COVID-19 Pandemic

In a guidance for pharmacies issued on May 28, the CDC updated its COVID-19 pandemic advice to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. Clinical services should be provided according to the Framework for Healthcare Systems Providing Non-COVID-19 Clinical Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic, CDC said. The document details considerations for balancing the need for non-COVID-19 care with the risk of patient harm if the care is not provided and the possibility of community transmission if patients receive clinical interventions.

Other points made by CDC in its updated guidance included the following:

- Implement universal use of face coverings by everyone in the pharmacy, including pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and all who enter the pharmacy. Medical or surgical masks for preferred health care professionals for source control; cloth face coverings should not be worn instead of a respirator or facemask if more than source control is required.

- Advise staff who are sick (fever or symptoms of COVID-19) to stay home and away from the workplace until they have recovered.

- During the prescription-filling process, maintain physical distancing and minimize the risk of exposure for pharmacy staff and patients. Follow CDC’s general workplace interim guidance and also provide hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol for patients, avoid handling paper prescriptions and insurance cards, and let older adults and other high-risk patients know about alternate delivery options.

- Use engineering and administrative controls to limit close contact between pharmacy staff and patients and among patients.

- Reduce risk during COVID-19 testing and other close-contact pharmacy services.

- Provide adult vaccinations based on local conditions. Additional advice on immunizations is expected from the CDC.

REFERENCES

Collins FS, Stoffels P. Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV): an unprecedented partnership for unprecedented times [editorial]. JAMA. 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8920 [Epub ahead of print]

DeRoo SS, Pudalov NJ, Fu LY. Planning for a COVID-19 vaccination program. JAMA. 2020 May 18. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8711 [Epub ahead of print]

Parks JM, Smith JC. How to discover antiviral drugs quickly. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr2007042 [Epub ahead of print]

Zhu F-C, Li Y-H, Guan X-H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human trial. Lancet. 2020 May 22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31208-3 [Epub ahead of print]

Back to Top