Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

One of the most important roles for pharmacy technicians who participate in medication therapy management (MTM) is to develop and maintain the documents and paperwork involved in MTM. Pharmacists can focus more efficiently on patient care if they have administrative support from technicians. By starting out with the right types of documents and keeping them up to date, technicians can help to greatly streamline the MTM process.

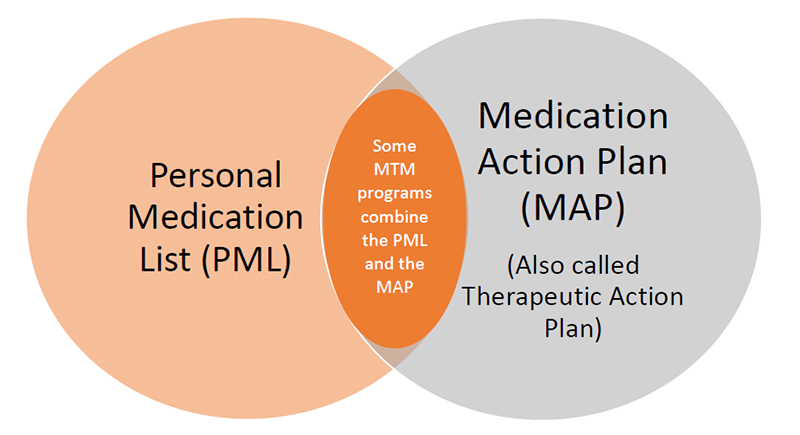

The main documents used in MTM are the Personal Medication List (PML) and the Medication Action Plan (MAP). These documents may be referred to by slightly different names, depending upon the pharmacy or healthcare institution. The terms used here are consistent with those used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). There are no standard “forms” used across all MTM practices. CMS provides suggested forms, noting that they can be adapted for the practice setting. This module will suggest some ways that MTM documents can be tailored to fit the needs of your practice setting.

1. THE PERSONAL MEDICATION LIST (PML)

In addition to PML, this document may be referred to as a Patient–Centered Medical Record (PMR), Patient–Centered Medication List, or other names. Its goal is to provide a user–friendly listing of all the patient’s current medications. The PML should contain additional information to help the patient take medications correctly, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Essential Information in Personal Medication List

The PML is different from other types of documents the pharmacy can provide for patients. Most pharmacy computer systems are capable of generating only transaction records and standard drug information handouts. In many pharmacy settings, a patient would need an MTM consultation in order to receive a document as individualized and comprehensive as the PML.

There are a number of sample templates available for generating an electronic PML. However, no one template is suitable for every pharmacy setting. A particular pharmacy chain or clinic may have its own PML template. The pharmacy staff may create their own form or adapt an existing document for the purposes of MTM. Some outside MTM organizations provide specific templates to use. The technician participating in MTM may want to ask the following questions:

- Does our pharmacy have a template for the PML?

- Is our PML working for us? Are there changes that can be made to ease the process of generating or updating the PML?

- Are there changes that can be made to improve the PML’s usefulness for the patient?

Drawbacks of some available PML templates include:

- Providing too much information makes the PML difficult or unrealistic for the patient. An example of this might be the discharge paperwork provided to patients when they leave the hospital. If drug information is too complex, or is buried within a multi–page document loaded with instructions and fine print, it is likely to be ignored by the patient.

- Providing too little information on the PML does not help patients to make better use of their medications. For example, a basic listing of medication names and doses does not help patients to understand why they are using the drug.

- Too complicated: Having too many columns or spaces for information can be a source of confusion for patients and provides extra work for the pharmacy technician.

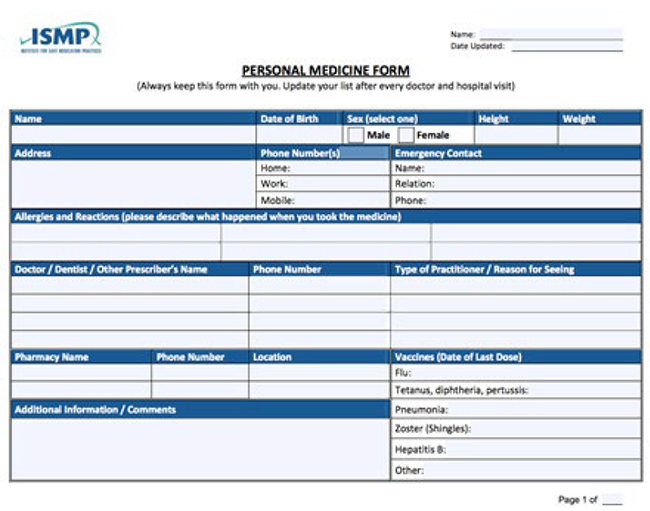

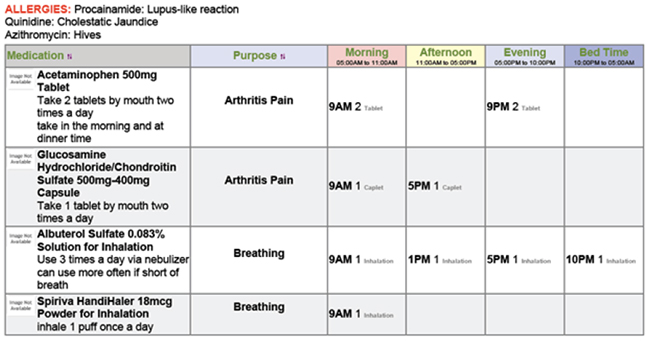

A PML template provided on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) website is shown in Figure 2.1 This basic template provides key information needed in the PML, but it may lack the flexibility needed for some pharmacy MTM services. Another example of the PML in a fillable PDF format (shown in Figure 3) is available from the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) at https://www.ismp.org/tools/personal_med_form/Personal_Medicine_List.pdf.

| Figure 2. CMS Recommended Format for the Personal Medication List |

| Personal Medication List for: Mary Andrews DOB: 12/1/1950 |

| This medication list was made for you after we talked. We also used information from: |

Dr. Robert Barnard

Mountainview Hospital |

• Use blank rows to add new medications. Then fill in the dates you started using them.

• Cross out medications when you no longer use them. Then write the date and why you stopped using them.

• Ask your doctors, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers to update this list at every visit. |

Keep this list up to date with: |

• Prescription medications

• Over the counter drugs

• Herbal supplements

• Vitamins

• Minerals |

| If you to go the hospital or emergency room, take this list with you. Share this with your family or caregivers too. |

DATE PREPARED:

November 1, 2020 |

| Allergies or Side Effects: None |

| Medication and Dose: Lasix (Furosemide) 80 mg tablets |

| How I use it: Once daily in the morning, by mouth. May be taken with or without food. |

| Why I use it: Loop diuretic. Prevents fluid retention |

Prescriber: Dr. Robert Barnard |

| Additional instructions: Furosemide will make you urinate more often. Try to avoid becoming dehydrated. Follow instructions about using potassium supplements and getting enough salt and potassium in your diet. Drink plenty of fluids. |

| Date I started using it: 11/1/2018 |

Date I stopped using it: (Not applicable) Do not stop taking this medication unless advised by a healthcare professional. |

| Why I stopped using it: |

| Medication: Toprol (metoprolol succinate), 100 mg |

| How I use it: Once daily in the morning, by mouth. May be taken with or without food. |

| Why I use it: Beta blocker for treatment of mild heart failure. Lowers blood pressure. |

Prescriber: Dr. Robert Barnard |

| Additional instructions: Do not chew or crush this tablet. May cause dizziness that can lead to falls. Check your blood pressure in one week; report to doctor or MTM pharmacist if blood pressure is above 140/86. |

| Date I started using it: 10/15/2020 |

Date I stopped using it: (N/A). Do not stop taking this medication unless advised by a healthcare professional. |

| Why I stopped using it: |

| Figure 3. Sample PML Form from Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) |

|

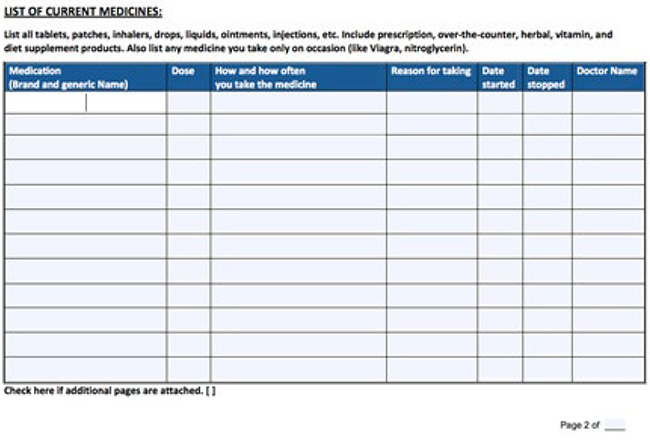

In general, is important to keep information and forms in MTM as patient–specific as possible. For example, type size may be increased for persons with visual impairments. Some patients may find it useful to be able to see the drug listing organized by their medical condition (e.g., “On top are the medications I take for my heart”). However, most prefer to have the PML organized by the time of day the medication is taken. This helps the person to see at a glance what they’ll need to be doing to prepare for and take medications correctly (Figure 4).

| Figure 4. Sample PML Layout By Time of Day |

Personal Medication List for Jane Smith

Please share this list with all your healthcare providers

Doctor: John London (Primary care) [Phone]

Doctor: Barbara Wong (Pulmonologist) [Phone] |

A Patient–Centered PML:

Organizes the information in a patient–centered manner

Includees space for action items or reminders, if possible |

o By health condition or indication; or by time of day the medication is taken

o Has the flexibility to be printed in the manner the patient finds most helpful

o Use symbols, pictures (e.g., image of a tablet, if branded). Standard symbols can be used to represent the time of day the dose is taken (e.g., morning, noon, evening, bedtime) |

| Focuses on health literacy |

o Do not overuse technical or legal terms or disclaimers, etc.

o Do not use medical terms a patient would have difficulty understanding (e.g., calling a drug an "antipyretic" rather than a fever reducer)

o Do not overuse acronyms (avoid acronyms, abbreviations, or symbols that may be unfamiliar to the patient or create confusion) |

THE PATIENT’S ROLE IN MAINTAINING AN ACCURATE PML

In order to be effective, MTM documents must be realistic with regard to how the patient is willing and able to use them. Ideally, the goal is to develop documents and tools that allow patients to manage their health conditions with less effort.

Sometimes, the job of keeping the PML up–to–date is expected to fall to the patient. This may not be realistic. Instructions in the CMS documents on MTM suggest that patients 1) fill in any new medications and their start dates on the PML; 2) share the PML with doctors and family members; 3) ask providers to help update the PML during each healthcare visit.

It is logical that some patients will carry out these steps faithfully. Others may lack the capacity to do so, or start out well but fall off over time. Updating the PML may be particularly challenging for patients who have multiple chronic health problems. It can be difficult to keep up with blood test and radiology results, physician and/or therapy appointments, and complex daily medication regimens. In many situations, patients will require family or caregiver support to effectively manage their medications. When developing the PML, the pharmacy team conducting MTM should have realistic expectations and be aware of differences among individual patients.

HOW CAN TECHNICIANS HELP TO GENERATE AND UPDATE THE PML?

There are a number of ways technicians can be involved in generating and updating the PML. Depending on the pharmacy setting and the technician’s training, the technician may be a part of the initial patient interviews, gathering information about what drugs they are using and how they are being used. The technician can start filling in the PML template before, during, or after an MTM session and use the information gathered during the patient interview to generate a more accurate list for the pharmacist to review. Technicians may be involved in verifying medications through a second reliable source, such as a caregiver. Technicians may be involved in updating the PML as the patient’s condition or medications change, providing current copies to prescribers and other members of the healthcare team, and explaining to patients how the PML can be used.

2. THE THERAPEUTIC ACTION PLAN

Another key document used in MTM is the Therapeutic Action Plan, also called the Medication Action Plan or MAP. The aim of this document is to identify the goals of MTM, including changes made in medications or other actions to help resolve patients’ health problems and/or to meet specific health objectives. The Therapeutic Action Plan is a key part of the strategy in MTM because it documents the ultimate goals of the MTM service. Technicians who participate in MTM should be familiar with the format and purpose of this document, how to incorporate changes or updates, and who should receive copies of the Therapeutic Action Plan.

The Therapeutic Action Plan will be different for every patient, but there are some common assessment points, summarized in Table 1. This checklist, modified for the patient’s specific health conditions, can serve as a basis to identify the patient’s medication–related problems, adherence problems, and potential health safety issues or behavioral risks. Most of these questions should be assessed by the pharmacist during the face–to–face MTM interview, but the technician should be aware of these objectives to understand the overall purpose of MTM. While the technician may record the information, the document is ultimately the responsibility of the pharmacist.

| Table 1. Developing the Therapeutic Action Plan: Points to Consider2-4 |

| Question for the Patient: |

Assessment Points for MTM |

What medications are you taking?

How do you take this medication? |

• Adherence to the medication

• Unnecessary or duplication of therapy

• Appropriateness of dose, frequency, route of administration

• Possible contraindications to the medication

• Is the regimen too complicated? (e.g., multiple doses per day)

• Are dosage instructions being followed? (e.g., take with food) |

| What is this medication used for? |

• How committed is the patient to the need/ rationale for this particular therapy?

• Does the patient plan to discontinue the drug when he/she feels better and "doesn't need it"? |

| What problems are you having related to this medication? |

• Potential drug interactions/allergies

• Adverse drug reactions

• Concerns about serious complications (e.g., blood clots)

• Complex administration method (e.g., injected medications) |

| What is your chief complaint or main health problem at this time? What is the number-one thing I can help you with today? |

• Untreated medical conditions that require treatment

• Instructions from the physician that the patient does not understand

• Copayments are too high |

| Therapeutic alternatives |

• Therapies that may prevent an adverse reaction (e.g. antiemetics) or disease complication

• Potentially safer medications

• Dosage forms/devices that increase convenience (e.g., autoinjector, patch)

• Potential cost savings |

| Wellness issues |

• Immunizations

• Preventive care and screening (e.g., mammography, cholesterol screening, colonoscopy)

• Smoking and substance abuse cessation

• Exercise habits, weight loss

• Nonpharmacologic approaches (e.g., physical therapy, rehabilitation therapies) |

SUMMARIZING THE THERAPEUTIC ACTION PLAN FOR THE PATIENT

Goals of the Therapeutic Action Plan include:

- Help motivate the patient to assist in managing his or her own health

- Develop practical steps for the patient and healthcare team to follow

- Identify and correct problems or errors related to medication safety

- Explore ways to reduce costs: reduce waste, improve adherence, offer less-expensive drug alternatives when possible

The Therapeutic Action Plan will list recommended steps that may be implemented by the patient, caregivers, or the physician. The physician may need to approve or review some changes before an Action Plan can be distributed to the patient.

The Action Plan should be provided to the patient in writing, either as a separate document or integrated with the PML. Newer formats may allow patients to access and manage this information via their smartphones or other electronic devices. For example, some people with certain chronic disease are using specialized “apps” to keep symptom diaries and log medication dosage or adverse effects. The pharmacist may discuss with the patient how steps from the Therapeutic Action Plan can be integrated into these systems. Some MTM services can be set up to print the PML and Therapeutic Action Plan in multiple formats, such as an abbreviated wallet–card version plus a standard–sized sheet to post on a bulletin board or refrigerator.

To simplify the goals for the patient, many Therapeutic Action Plans present the information to the patient in the following format:

- What we talked about (during MTM)

- What I need to do

- What I did, when I did it

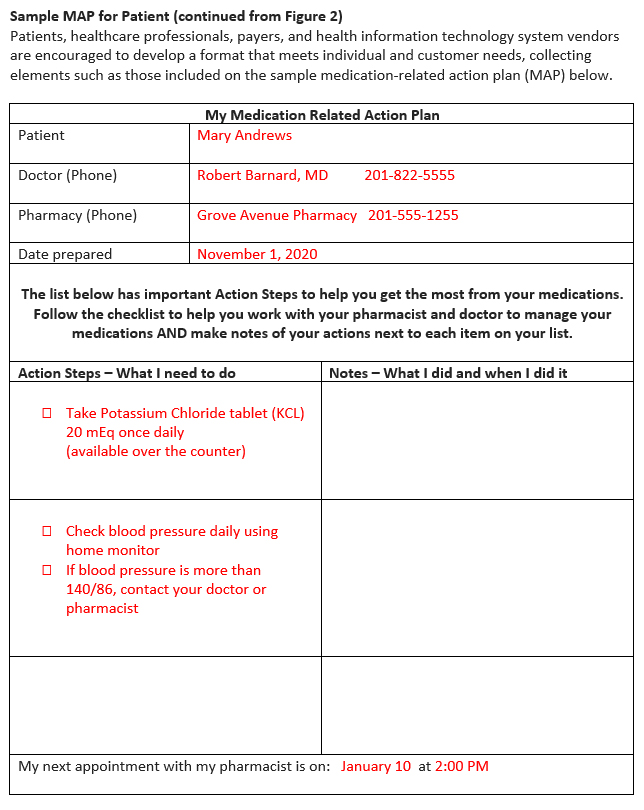

A sample of the CMS action plan (called the Medication Action Plan, or MAP) format is shown Figure 5.

| Figure 5. CMS Medication-Related Action Plan (MAP) |

|

Some MTM services combine the Personal Medication List and the Action Plan into one document. This combined document would review the patient’s current medications and indicate changes or actions that are decided during MTM. This allows the patient to have a record of existing medications and actionable items, all in one place.

FOLLOWING UP TO THE THERAPEUTIC PLAN

MTM should not be a one–time process. Follow–up, or “continuity of care,” is especially important for managing chronic disease. Giving patients positive steps or goals may encourage them to return for follow–up visits. A person who is not engaged in the process—or who does not believe he or she has gained any benefit from MTM—is less likely to return for follow–up.

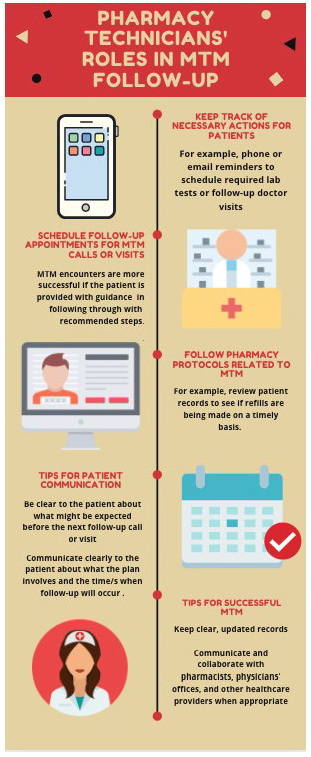

Technicians can serve essential roles in ensuring follow–up with MTM, as outlined in the diagram in Figure 6.

| Figure 6. Pharmacy Technicians' Roles in MTM Follow-up |

|

DOCUMENTATION TIPS

Documentation is an essential part of MTM. In addition to providing information for the patient, records of the MTM process must be generated for the pharmacy and for other healthcare providers. MTM encounters are usually documented using software provided by the pharmacy. In an ideal world, this documentation would automatically be transferred to the patient’s Electronic Health Record (EHR) where updates would be visible for all providers. Unfortunately, not every system is equipped with effective EHRs. Sometimes, documents must be exchanged between physicians’ offices or hospitals via fax or secure email.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The PML and the Therapeutic Action Plan (or similar documents) are standard parts of most MTM settings. Generating printed lists with a lot of information and handing them over to the patient is unlikely to achieve the goals of MTM. Directions should be presented in ways that are clear, concise, and easy to use for the patient. Follow–up with healthcare providers to document the decisions made during MTM is vital to the process of health information exchange among providers. Pharmacy technicians are an essential part of the documentation process. Pharmacists and technicians who engage in MTM should evaluate existing documents and determine how they can be adapted to advance the MTM process.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medication Therapy Management Program Guidance and Submission Instructions. May 22, 2020. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/memo-contract-year-2021-medication-therapy-management-mtm-program-submission-v-052220.pdf.

- Stebbins MR, Cutler TW, Parker PL. Assessment of Therapy and Medication Therapy Management. In: Alldredge BK, Corelli RL, Ernst ME, et al. Koda-Kimble and Youngs Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs. 10th ed. Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

- American Pharmacists Association and the National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. Medication Therapy Management in Pharmacy Practice: Core Elements of an MTM Service Model. Version 2.0. 2008.

- Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC). Defining the Medical Home. Available at: https://www.pcpcc.org/about/medical-home.