Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

INTRODUCTION

Vaccinations are an important aspect of preventative health, particularly for older adults. Individuals aged ≥65 years represent a susceptible population, at higher risk for complications of vaccine-preventable illness and death. Vaccination against communicable diseases, such as pneumococcal disease and influenza, is an invaluable and often underutilized health care tool that can decrease morbidity and mortality in the older adult population. In the era of COVID-19, it is critically important that older patients, especially those with comorbidities and other risk factors, maintain vaccination schedules in a safe environment.

Health care professionals have an opportunity to influence vaccination rates and to educate patients about the importance of maintaining recommended immunization schedules. Engaging in shared decision-making about vaccinations, and offering safe, alternative administration options during the COVID-19 pandemic can reassure patients who might otherwise be reluctant to get recommended vaccinations.

Interprofessional Collaboration

Q1. How can the members of the care team work together in the clinical decision-making process to improve pneumococcal and influenza vaccination rates in older adults?

Q2. How can pharmacists and nurses work together to improve vaccination rates among older adults in the community setting?

You can read the transcripts at the link provided at the end of the activity

|

SECTION 1: Vaccine Preventable Illnesses in Older Adults

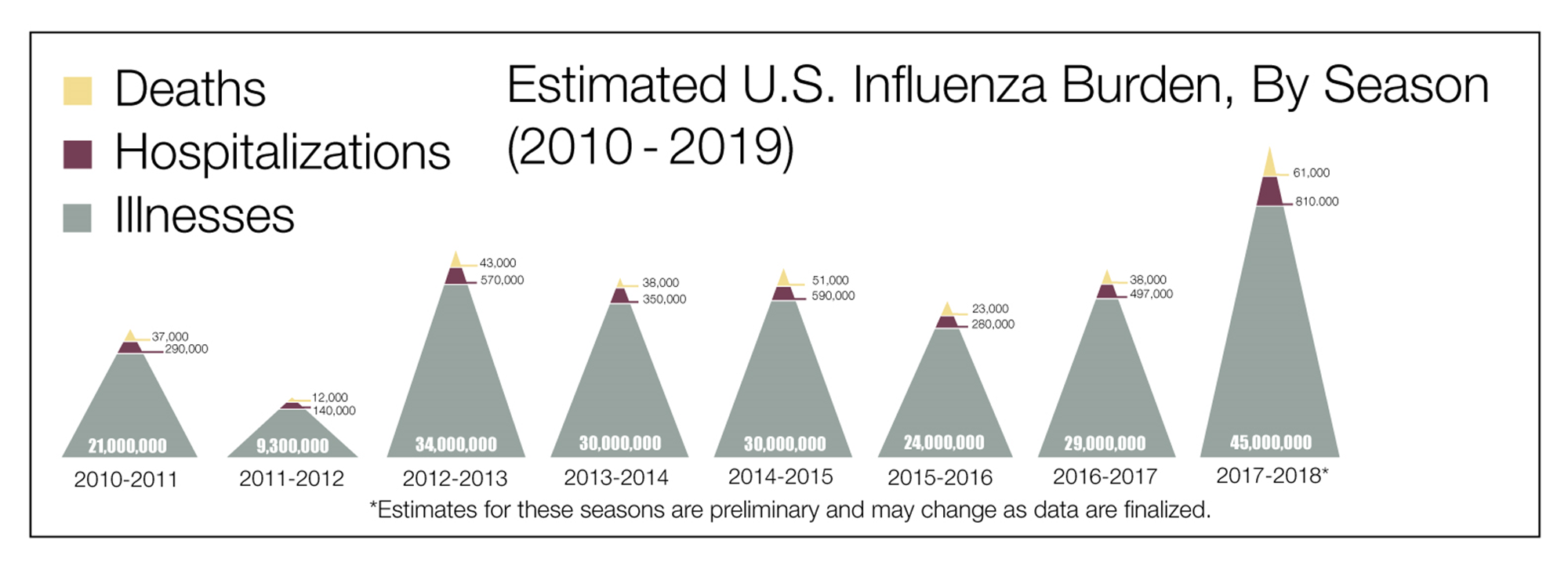

Vaccine-preventable illnesses continue to afflict our global society. In particular, influenza and pneumonia impose a major public health burden as a significant cause of morbidity, mortality, and economic loss in the United States (US). During the 2018─2019 influenza season, there were over 35.5 million illnesses, 16.5 million medical visits, close to 500,000 hospitalizations, and an estimated 34,000 deaths. This is generally consistent among influenza seasons (Figure 1).(CDC 2020A) Between October 2019 and April 2020, the CDC estimates are 9,000,000–56,000,000 flu illnesses; 410,000–740,000 flu hospitalizations; and 24,000–62,000 flu deaths.(CDC 2020B)

Older adults are disproportionately at higher risk for worse clinical outcomes related to influenza. Estimates from the same influenza season show adults aged ≥65 years make up only 8.7% of symptomatic illnesses and 10.4% of medical visits, but account for 57% of influenza-related hospitalizations and 74.8% of deaths due to influenza.(CDC 2020C) In 2017, there were an estimated 1.3 million emergency departments visits with a primary diagnosis of pneumonia and over 49,000 deaths.(Rui 2019) A pivotal study of active population-based surveillance for community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among adults observed the highest rates among the oldest adults – adults 65─79 years of age (63.0 cases per 10,000 adults) and 80 years or older (164.3 cases per 10,000 adults) compared to an overall annual incidence of 24.8 cases per 10,000 adults.(Jain 2015) Influenza and pneumonia remain a top-ten cause of death in the US with an overall estimated 17.1 deaths per 100,000 population and 92.1 deaths per 100,000 population for ages ≥65 years.(Heron 2019)(Xu 2020)

Figure 1. Estimated burden of influenza in the United States, 2010-2019 – deaths, hospitalizations, and illnesses.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease Burden of Influenza. Accessed July 20, 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html.(CDC 2020A)

Vaccines are one of the safest and most effective means of preventing disease. The benefit is especially notable for susceptible populations at higher risk for complications from vaccine-preventable illness such as influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia. Despite the significant risk of these vaccine-preventable illnesses in older adults, vaccine coverage rates are suboptimal among this high-risk group. Influenza vaccination coverage is estimated to be the highest for older adults compared to other age groups, but is still less than 70% coverage (68.1% for the 2018─2019 influenza season).(CDC 2020C)

Vaccination is the primary method to prevent illness and death from influenza.(Grohskopf 2019) Based on model estimates, a 5% increase in influenza vaccine coverage would result in 11,000 fewer hospitalizations.(Hughes 2020) Similarly with pneumococcal vaccination, the coverage rates remain relatively low for older adults. In a study by the CDC, claims data for pneumococcal vaccinations – 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) – for Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years were analyzed. Receipt of at least one of either PCV13 or PPSV23 ranged from 40% in 2010 to 59.3% in 2017. Claims for receipt of both vaccines, as recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) at that time, was estimated at only 23.8% in 2017.(CDC 2018) The large scale disease burden of these vaccine-preventable illnesses and recognition of the ability to enhance vaccine coverage represent an important area where health care professional education is needed.

The economic burden due to vaccine-preventable diseases for adults in the US is tremendous and was estimated by Ozawa and colleagues.(Ozawa 2016) The investigators examined economic loss due to inpatient and outpatient treatment costs, outpatient medication costs, and productivity loss to seek care. In one year, the total economic burden was approximately $9 billion from vaccine-preventable diseases related to 10 adult vaccines with unvaccinated adults accounting for close to 80% ($7.1 billion) of the burden. An estimated 65% ($5.8 billion) resulted from influenza and an additional 21% ($1.9 billion) from pneumococcal disease. For adults ≥65 years, influenza (55%) and pneumococcal disease (35%) yielded the most economic burden of the examined vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccines not only reduce the burden of individual morbidity and mortality, but mitigate the larger societal economic cost.(Ozawa 2016)

The general management of vaccine-preventable illness such as influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia involve principles and practices of prevention and treatment. Vaccines represent the most effective medical intervention – these recommendations are described in more detail in a later section. Treatment of influenza primarily involves initiation of antiviral therapy for patients with suspected or confirmed influenza.(Uyeki 2019) This recommendation applies directly to adults ≥65 years. Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia primarily involves antibiotic therapy with one or more agents with activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae.(Metlay 2019)

SECTION 2: Age-Related Changes in Immunity

Immunosenescense, which is described in the literature as age-associated changes in the immune system resulting in impaired immune responses, is largely linked to a diminished response to vaccines and an increased rate of morbidity and mortality due to infectious diseases.(Montecino-Rodriguez 2013)(Bandaranayake 2016) As life expectancy and the elderly population continue to increase, it is becoming more important for health care providers to understand the various changes the immune system undergoes in aging in order to provide the best possible preventative care to this patient population. Low level chronic inflammation, or inflammaging, is a hallmark of every major age-related disease. Inflammaging is characterized by persistent, but low-level, infiltration of the immune system with a heightened pro-inflammatory state characterized by elevated levels of certain pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and acute phase reactants.(Bandaranayake 2016)(Pinti 2016) Additionally, the following specific changes to the immune system are seen due to aging:(Castle 2007)(Pinti 2016)

- Ineffective apoptosis of healthy immune tissue preventing the production of new cells or impairing activity of those that need to undergo apoptosis

- Increased levels of circulating inflammatory mediators including pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute phase proteins such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) as markers of inflammaging

- Increased leptin hormone leading to increased adipose tissue, which is associated with an increased pro-inflammatory environment

- Altered functioning of neutrophils contributing to changes in the innate immunity which increases risk of acquiring infections

- Changes in antigen uptake, processing, and presentation along with functional defects of T cells leading to reduced antibody responses

- Changes in the number of immune receptors and altered signaling pathways

- Elevated baseline inflammation leading to intrinsic defects in T cells and B cells

- Altered function of T cells due to the deterioration of functional thymic compartments

- Reduction in the number of circulating B cells or decreased expression of B cells leading to reduced ability to generate antibodies

As a result of immunosenescense, elderly patients’ ability to generate an antibody response to certain vaccines such as influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or herpes zoster is also significantly affected compared to younger adults. Consequently, their inability to respond efficiently to infections can lead to an increased susceptibility to preventable infections such as influenza, pneumococci, respiratory syncytial virus, herpes zoster or other opportunistic infections leading to increased hospitalizations and deaths. Thus, there is a great need for health care providers to be aware of the effects of aging and the need for vaccines tailored to optimize the aged immune system response.

SECTION 3: Vaccine Recommendations in Older Adults

Both the pneumococcal and influenza vaccine schedules were updated in 2020; updates are summarized below.(CDC 2020D)

- Influenza update: Includes a bulleted list indicating when live attenuated influenza vaccine should not be used and minor edits to the guidance for persons with a history of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

- Pneumococcal update: Indicates the updated recommendations for vaccination of immunocompetent (defined in discussion as adults without an immunocompromising condition, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak, or cochlear implants) adults ≥65 years. One dose of PPSV23 is still recommended. Shared clinical decision-making is recommended regarding administration of PCV13 to immunocompetent persons ≥65 years.

Health care providers who recommend or administer vaccines can access all CDC recommended immunization schedules and footnotes at the CDC website or by using the CDC Vaccine Schedules mobile app; the link is available in the Resource section.

Pneumococcal Vaccines

The current ACIP/CDC guidelines for pneumococcal vaccination are complicated and often cause confusion. Additionally, shared decision-making is time consuming, and busy clinicians may refer to another health care provider. For example, in the inpatient setting, instructions for vaccinations may not be executed prior to discharge because the clinician has no way of ensuring a patient will receive the second dose of pneumococcal vaccine. They may refer the patient back to their primary care provider, who may, in turn, send the patient to a pharmacist in a community pharmacy. Uninsured patients may get some, but not all, vaccinations prior to discharge. The case example at the end of section 4 is intended to illustrate approaches to applying the guidelines for different patient scenarios.

The ACIP recommendation for pneumococcal vaccination in older adults was updated on November 22, 2019. The updated guidance no longer recommends routine use of PCV13 in series with PPSV23 for all non-immunocompromised adults ≥65 years. The pillar for change is the increase of PCV13 pediatric immunization resulting in historically low pneumococcal disease among adults through reduced carriage and transmission (Figure 2).(Matanock 2019)

Figure 2. Invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) incidence among adults aged ≥65 years, by pneumococcal serotype — United States, 1998–2017.(Matanock 2019)

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 Years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:1069–1075. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6846a5.htm.(Matanock 2019)

Recommendation Summary

- Administer a single dose of PPSV23 for adults aged ≥65 years.

- Use shared clinical decision-making for administration of PCV13 to adults aged ≥65 years who are not immunocompromised or have CSF leak or cochlear implants and who have not previously received PCV13.

- If the decision is made to administer PCV13, it should be administered first, followed by PPSV23 at least one year later.(Matanock 2019)

- If a patient received a PPSV23 vaccine prior to age 65, he/she should receive a second and final dose 5 years after the first dose.(CDC 2019A)

The rationale to administer PCV13 ≥1 year prior to PPSV23 is due to the added immune response when given in this particular order. The PCV13 is boosted by the PPSV23 and adults who receive immunizations in this order have a higher antibody response.(IAC 2020)

Clinical Considerations

The new ACIP guidance incorporates shared decision-making into use of the PCV13 for non-immunocompromised patients ≥65 years. Shared decision-making entails assessing an individual patient’s risk of exposure to PCV13 serotypes and the potential impact of underlying medical conditions on developing pneumococcal disease if exposure occurs.

If not previously vaccinated with PCV13 as an adult, the following categories of adults aged ≥65 may receive higher than average benefit and should use the shared decision-making model with their provider.(Matanock 2019)

- Persons residing in nursing homes or other long-term care facilities

- Persons residing in settings with low pediatric PCV13 uptake

- Persons traveling to settings with no pediatric PCV13 program

- Persons with the following chronic health conditions:

- Alcoholism

- Chronic heart disease and cardiomyopathies

- Chronic liver disease

- Chronic lung disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Smokers

- Those with more than one chronic health condition

All patients with cochlear implants, CSF leaks, asplenia, sickle cell disease, other hemoglobinopathies, or immunocompromising conditions should receive one dose of PCV13 vaccination if not previously vaccinated with PCV13.(CDC 2020E) PPSV23 should be given to patients in this population ≥8 weeks apart from PCV13 and ≥5 years from the last PPSV23 dose, if they received a prior PPSV23 dose.(Matanock 2019)

Immunocompromising conditions include chronic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, immunodeficiency, iatrogenic immunosuppression, solid-tumor or hematological malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplants, bone marrow transplant, congenital or acquired asplenia, sickle cell disease, or other hemoglobinopathies.(CDC 2019B)

If a patient has received PPSV23 at ≥65 years, and subsequently becomes a candidate for PCV13 after development of a new chronic health condition, OR is diagnosed with an immunocompromising condition AND has not had previous a PCV13 dose, give one dose of PCV13 at least one year after PPSV23.(Matanock 2019)

Contraindications to PCV13:

- Persons who have had a severe allergic reaction (e.g., anaphylaxis) after PCV7 or PCV13 or to any vaccine containing diphtheria toxoid.(CDC2019A)

- Persons with a severe allergy to any component of PCV13 vaccine.(CDC 2019A)

Contraindications to PPSV23:

- Persons who have had a severe allergic reaction (e.g., anaphylaxis) to a previous dose.

- Persons with a severe allergy to any component of PPSV23 vaccine.(CDC 2019A)

If the provider and patient deem the benefits outweigh the risks, PCV13 or PPSV23 may be administered to patients with moderate or severe acute illness with or without fever.(CDC 2019A)

Influenza Vaccines

As a result of immunosenescense, two types of influenza vaccines are offered specifically for adults aged ≥65 years. Neither vaccine is preferred over the other based on ACIP recommendations. This population should NOT receive a nasal spray vaccine.

High-dose flu vaccine: The high-dose flu vaccine contains four times the amount of antigen and is associated with a higher antibody production. Adults aged ≥65 who received the high-dose vaccine had 24% fewer influenza illnesses compared to those who received the standard flu dose.(CDC 2020F)

Adjuvanted flu vaccine: The adjuvanted flu vaccine contains MF59 adjuvant which creates a stronger immune response. MF59 is an oil-in-water emulsion of squalene oil which is a naturally occurring substance found in humans, animals and plants. It can also reduce the amount of virus needed for production of a vaccine, which provides ability to manufacture greater supplies of vaccine.(CDC 2019C)

High-dose and adjuvanted flu vaccines may result in increased mild side effects compared to standard-dose influenza vaccines. Side effects can include pain, redness or swelling at the injection site, headache, muscle ache and malaise which typically resolve in 1-3 days.(CDC 2020F)

Recommendation Summary

Clinicians can administer PCV13 or PPSV23 at the same time as the influenza vaccine. Each vaccine should be administered with a separate syringe and when feasible, at a different injection site.(CDC 2019D)

Contraindications to Influenza Vaccine:

Severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) to egg protein or any previous dose of any influenza vaccine is a contraindication to adjuvanted and high-dose influenza vaccines.

Patients with a history of egg allergy manifesting as urticaria may receive influenza vaccine. However, if egg allergy causes angioedema, swelling, respiratory distress, recurrent emesis, or if the patient previously required epinephrine or another emergency medical intervention for anaphylaxis, he/she should be vaccinated in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting by a health care provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions.(CDC 2019E)

Precautions according to package inserts for influenza vaccines should be considered for Guillain-Barre Syndrome that occurred within 6 weeks of receipt of prior influenza vaccines.(Fluad PI 2020)

Vaccination providers should check FDA-approved prescribing information for 2020─2021 influenza vaccines for the most complete and updated information, including (but not limited to) indications, contraindications, warnings, and precautions. Package inserts for US-licensed vaccines are available at https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/approved-products/vaccines-licensed-use-united-statesexternal icon.

Box 1. Clinical Pearls

- Never administer PPSV23 and PCV13 at the same time.

- The CDC recommends adults receive one dose of PCV13 if indicated and if they have not received PCV13 previously.(CDC 2020G)

- COVID-19 resulted in a decrease of non-influenza childhood vaccine.(Santoli 2020) Given the link between pneumococcal disease in older adults and childhood PCV13 immunization rates, the latter should be incorporated into the shared decision-making model.

- If both vaccines are to be delivered, does PPSV23 have to be delivered exactly one year after PCV13? While it is assumed the ACIP refers to a calendar year, the Immunization Action Coalition states that delivery of PPSV23 a few days/weeks early is not a medical problem, but may be an insurance reimbursement issue.(IAC 2020)

- If a patient cannot recall if they received pneumococcal vaccines and records cannot be obtained, vaccines should be delivered. Per the CDC Best Practices for Immunization Guidelines, self-reported doses of influenza or PPSV23 are acceptable and all other vaccines should be accepted only with dated records.(Ezeanolue 2020)

- You can administer PCV13 or PPSV23 at the same time as the influenza vaccine.(CDC 2019D)

|

Clinical Barriers and Solutions

- Time: Shared decision-making takes time. This may cause providers in the inpatient setting to refer to primary care providers and primary care providers to refer to pharmacies. Use of technology is one tool to overcome the time barrier. In addition to the immunization schedule app mentioned earlier, the CDC created a mobile app that helps vaccination providers quickly and easily determine which pneumococcal vaccines a patient needs and when. The app incorporates recommendations for all ages.(PneumoRecs 2020) The link to the app can be found in the Resources section. A second solution is training RNs and support staff on the use of such tools and guidelines so that patients may be presented to providers with recommendations. This saves time and allows the provider to focus on shared decision-making rather than calculation of PCV13 and PPSV23 series administration. Teaching institutions may utilize students to prepare immunization recommendations prior to patient appointments. Students and designated staff can also counsel patients on the risks/benefits of recommended immunization. COVID-19 has brought about an uptake in delivery of health care through telehealth. Students/support staff can virtually connect with patients to engage in shared decision-making prior to their appointment with the provider. The ACIP offers shared-decision making recommendations, including for the PCV13 for adults ≥65 years who do not have an immunocompromising condition, CSF leak, or cochlear implant. The link to their website is listed in the Resources section.(ACIP 2020)

- Cost: Medicare Part B covers 100% of the cost for both PPSV23 and PCV13 when administered at least 1 year apart and most private health insurance policies cover this vaccine.(CDC 2019F) Support staff or students can be trained to review the schedule prior to patients’ appointments to determine who may be candidates for pneumococcal vaccines. Calling or connecting virtually with patients prior to the visit to advise them to contact their insurance to ensure vaccine coverage may improve the patient experience.

- Pharmacists should be prepared to administer pneumococcal vaccines. The cost of stocking pneumococcal vaccines may be prohibitive for smaller primary care practices.

SECTION 4: Health Care Providers’ Roles in Improving Vaccination Rates in Older Adults

Physicians, advanced practice providers, pharmacists and nurses can all contribute to improving vaccination rates and supporting recommended vaccination schedules in a variety of settings.

Physicians/Advanced Practice Providers play a vital role in ensuring both the health of their patients and the public health. This is done by tracking the patient’s immunization history and ensuring they are up to date on all their vaccinations based on their needs. Educating the patient regarding the importance of certain vaccines and their risks/benefits is also an important role in both the outpatient and the inpatient settings.

Pharmacists play a number of roles including educating patients on the safety and benefits of vaccination, being members of the clinical team and identifying patients appropriate to receive vaccinations (e.g., ambulatory care pharmacists). Community pharmacists are the most accessible health care provider, both in physical proximity and overall access (i.e., no need for appointments, you can walk into a pharmacy and ask questions and get educated for free, etc.). Community pharmacists, therefore, are key to providing patient education and facilitating or administering vaccines in community pharmacies. In light of missed medical appointments due to COVID-19, pharmacists should assess vaccine status with patients to identify missed immunizations.

Nurses are able to follow standing orders for vaccines for older adults. Tools for implementing standing orders can be found at the Immunization Action Coalition website, https://www.immunize.org/standing-orders/. Practices for shared decision-making conversations and protocols can be created in both the inpatient and outpatient settings.

Support staff, students on clinical rotations and other delegates can gather information regarding vaccinations and engage in communication around shared decision-making so that the information is available when the patient presents to providers, thereby saving time.

CASE 1: Immunization and shared decision-making with older adults

CASE 1: James, a 66-year old male, presents for an annual wellness visit after his primary care provider’s office reopened to routine care during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is October 1, 2020. He has no underlying chronic illnesses, is not immunocompromised and is a non-smoker. He has not received any previous doses of PCV13 or PPSV23.

PAUSE AND REFLECT: Assess case questions based on content thus far, then listen to faculty commentary and read the transcripts at the link provided at the end of the activity.

Q1. How is shared decision-making implemented to determine the pneumococcal vaccine series?

Q2. Is PPSV23 indicated for James?

Q3. Should he receive PCV13 today?

Q4. What about influenza vaccine – is this indicated today?

Q5: If James had received a PPSV23 at age 62, what would be indicated today?

Q6: What resources can be utilized prior to the provider entering the patient room to obtain information from the patient and provide patient education?

CASE 1, continued: At our visit today through shared decision-making, we decide that James will receive one dose of PPSV23 and will not receive PCV13. Two years later James presents for his annual wellness physical and has a new diagnosis of Hodgkin disease.

PAUSE AND REFLECT: Assess case question based on content thus far, then listen to faculty commentary and read the transcripts at the link provided at the end of the activity.

Q7: Should James receive PCV13 despite receiving PPSV23 two years ago?

CASE 2: Immunization and shared decision-making with older adults

CASE 2: Joe is 66 years old and received a PPSV23 vaccine at age 64. He has no chronic illness, is non-immunocompromised and has smoked 1 pack of cigarettes a day for 8 years. He is visiting his primary care provider for his annual wellness visit. Flu season has already begun in Joe’s area.

PAUSE AND REFLECT: Assess case questions based on content thus far, then listen to faculty commentary and read the transcripts at the link provided at the end of the activity.

Q1: Should Joe receive a PCV13 vaccination today?

Q2. When should he receive PPSV23 if he received a prior PPSV23 dose at age 64?

Q3: What about influenza?

CASE 3: Immunization and shared decision-making with older adults

CASE 3: Sonia is 66 years old, has received no pneumococcal vaccines, has no chronic illness, is non-immunocompromised and a nonsmoker. Through shared decision-making incorporating both anecdotal reports at Sonia’s primary care provider’s office and CDC-reported NORMAL rates of non-influenza pediatric vaccine due to COVID-19, Sonia and her health care provider agree that she will NOT receive PCV13 today, but will receive PPSV23.

PAUSE AND REFLECT: Assess case questions based on content thus far, then listen to faculty commentary and read the transcripts at the link provided at the end of the activity.

Q1: Does Sonia receive a second and final dose of PPSV23?

Q2: What strategies can clinicians adopt to save time and facilitate vaccine administration?

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way that health care providers operate and has reduced the use of routine medical services, including vaccinations.(CDC 2020F) In order to protect individuals and communities from vaccine-preventable diseases, immunization services should be maintained and safe, alternative settings (e.g., home vaccination, in-car vaccinations) made available for vaccine administration. The CDC recommends that adult patients continue to receive vaccines according to the Standards for Adult Immunization Practice. Clinicians can communicate to patients the importance of maintaining vaccination schedules as well as reassure those who may be hesitant to present for vaccination visits. This is especially important among older adults and adults with underlying medical conditions who are at increased risk for preventable diseases and complications if vaccination is deferred.(CDC 2020H)

Maintaining immunization schedules is especially important in order to reduce the burden of respiratory illness and secondary infection with pneumococcus during upcoming influenza season. The CDC notes, “Routine vaccination prevents illnesses that lead to unnecessary medical visits, hospitalizations and further strain the health care system. For the upcoming influenza season, influenza vaccination will be paramount to reduce the impact of respiratory illnesses in the population and resulting burdens on the health care system during the COVID-19 pandemic.”(CDC 2020H) A key component of the public health response to COVID-19 is to have a health care system equipped to manage the surge of COVID-19 cases. Using long-standing preventative measures and vaccines against influenza and pneumococcal disease is a practical and important way to reserve the health care system for acute care related to COVID-19. It can also potentially help prevent COVID-19 and co-infections with such preventable diseases, a concern that health care providers have as we enter influenza season during COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, while the pneumococcal vaccines cannot prevent COVID-19 associated pneumonia, knowing vaccine status can help differentiate influenza, pneumococcus, or COVID-19 as the etiology of respiratory symptoms or pneumonia, which may all present with similar symptoms.(WHO 2020)

The CDC offers a number of guidance documents and other resources at the sites listed in the Resources sections of this monograph.

Resources

SUMMARY

Older adults are vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases, including pneumococcal disease and influenza. Vaccines are the most effective way to reduce the risk of acquiring the disease or developing complications that can lead to hospitalization, and even death. Engaging patients in a shared decision-making process within the context of the most recent adult immunization recommendations can improve vaccine coverage.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created multiple challenges within the health care system and older adults may be hesitant about visiting health care facilities for routine care, such as vaccinations. The interprofessional team can work together to maintain the delivery of critical health services, including patient support, education and alternative administration sites for recommended vaccines.

REFERENCES

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). ACIP Shared Clinical Decision-Making Recommendations. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/acip-scdm-faqs.html.

- Bandaranayake T, Shaw AC. Host resistance and immune aging. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(3):415─432.

- Castle SC, Uyemura K, Fulop T, Makinodan T. Host resistance and immune responses in advanced age. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23(3):463─479.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Adults: Protect Yourself with Pneumococcal Vaccines. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/features/adult-pneumococcal/index.html. [CDC 2019F]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Flu Vaccine with Adjuvant. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/adjuvant.htm. [CDC 2019C]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). People 65 year and Older and Influenza. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/65over.htm. [CDC 2020F]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumococcal Vaccine Recommendations. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/recommendations.html. [CDC 2019A]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumococcal Vaccine Timing for Adults. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/downloads/pneumo-vaccine-timing.pdf. [CDC 2020D]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations, Scenarios and Q&As for Healthcare Professionals About PCV13 for Adults. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/PCV13-adults.html. [CDC 2019B]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease Burden of Influenza. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. [CDC 2020A]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2018–19 Influenza Season. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm. [CDC 2020B]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu Vaccine with Adjuvant. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/adjuvant.htm. [CDC 2019E]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths in the United States — 2018–2019 influenza season. Accessed July 20, 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/2018-2019.html. [CDC 2020C]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Schedules. Schedule Changes & Guidance. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/schedule-changes.html#adult. [CDC 2020D]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal Vaccination Among U.S. Medicare Beneficiaries Aged ≥65 years, 2009-2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/pcv13-medicare-beneficiaries.html. [CDC 2018]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination Guidance During a Pandemic. 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pandemic-guidance/index.html. [CDC 2020G]

- Centers for Disease Control. Administering Pneumococcal Vaccines. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/administering-vaccine.html. [CDC 2019D]

- Ezeanolue E, Harriman K, Hunter P, et al. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/downloads/general-recs.pdf.

- FLUAD package insert. Available at https://www.fda.gov/media/94583/download. [Fluad PI 2020]

- Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2019-20 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2019;68(3):1─21. Published 2019 Aug 23.

- Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68 no 6. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2019. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_09-508.pdf.

- Hughes MM, Reed C, Flannery B, et al. Projected population benefit of increased effectiveness and coverage of influenza vaccination on influenza burden in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(12):2496─2502.

- Immunization Action Coalition. Pneumococcal Vaccines (PCV13 and PPSV23). Available at https://www.immunize.org/askexperts/experts_pneumococcal_vaccines.asp. [IAC 2020]

- Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. Adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):415─427.

- Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, et al. Use of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1069–1075.

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):e45─e67.

- Montecino-Rodriguez E, Berent-Maoz B, Dorshkind K. Causes, consequences, and reversal of immune system aging. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(3):958─965.

- Ozawa S, Portnoy A, Getaneh H, et al. Modeling the economic burden of adult vaccine-preventable diseases In the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2124─2132.

- Pinti M, Appay V, Campisi J, et al. Aging of the immune system: focus on inflammation and vaccination. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:2286─2301.

- PneumoRecs VaxAdvisor Mobile App for Vaccine Providers. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/hcp/pneumoapp.html. [PneumoRecs 2020]

- Rui P, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 emergency department summary tables. National Center for Health Statistics. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf.

- Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine pediatric vaccine ordering and administration — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:591─593.

- Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 Update on Diagnosis, Treatment, Chemoprophylaxis, and Institutional Outbreak Management of Seasonal Influenza [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2019 May 2;68(10):1790]. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):e1─e47.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public: Mythbusters. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters.

- Xu JQ, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 355. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db355-h.pdf.

Back to Top