Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

From Topicals to Biologics: The Evolution of Atopic Dermatitis Treatment and Pharmacist Implications

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacists—whether they are aware of it or not—see people with atopic dermatitis (AD) every day. More than 30 million Americans have AD. Its annual estimated cost exceeds $5 billion in prescription costs, hospitalizations, and physician visits. AD primarily affects children, but a significant number of adults are affected—a fact that is not well known but substantiated by research.1,2 Treatment failure is a leading concern in patients who have AD, and can be directly traced to poor adherence, treatment complexity, and formulary access. For this reason, pharmacists need to be familiar with the condition and actively discuss its treatment with affected patients.

Eczema is an umbrella term for a set of chronic inflammatory skin conditions. AD, a common type of eczema, is a chronic, inflammatory skin disease that affects patients of all ages.3 Despite its relatively high prevalence, AD is under-recognized as a chronic disease and is often either undertreated or treated inappropriately.4 Management of AD centers around several core goals: providing symptomatic relief, controlling AD manifestations, minimizing triggers or predisposing factors, and preventing future exacerbations.5

Fortunately, most people with AD (about 70%) have mild disease, usually treatable in primary care settings.6 For patients with mild-to-moderate AD, topical corticosteroids have been treatments’ mainstay since the 1950s.7 However, topical corticosteroids have been associated with poor adherence, a perception of high rates of adverse effects, insufficient clinical response, and concerns about long-term chronic use.8-10 For patients with moderate-to-severe disease refractory to topical therapies, phototherapy and systemic immunomodulators are options.11

Waxing, Waning

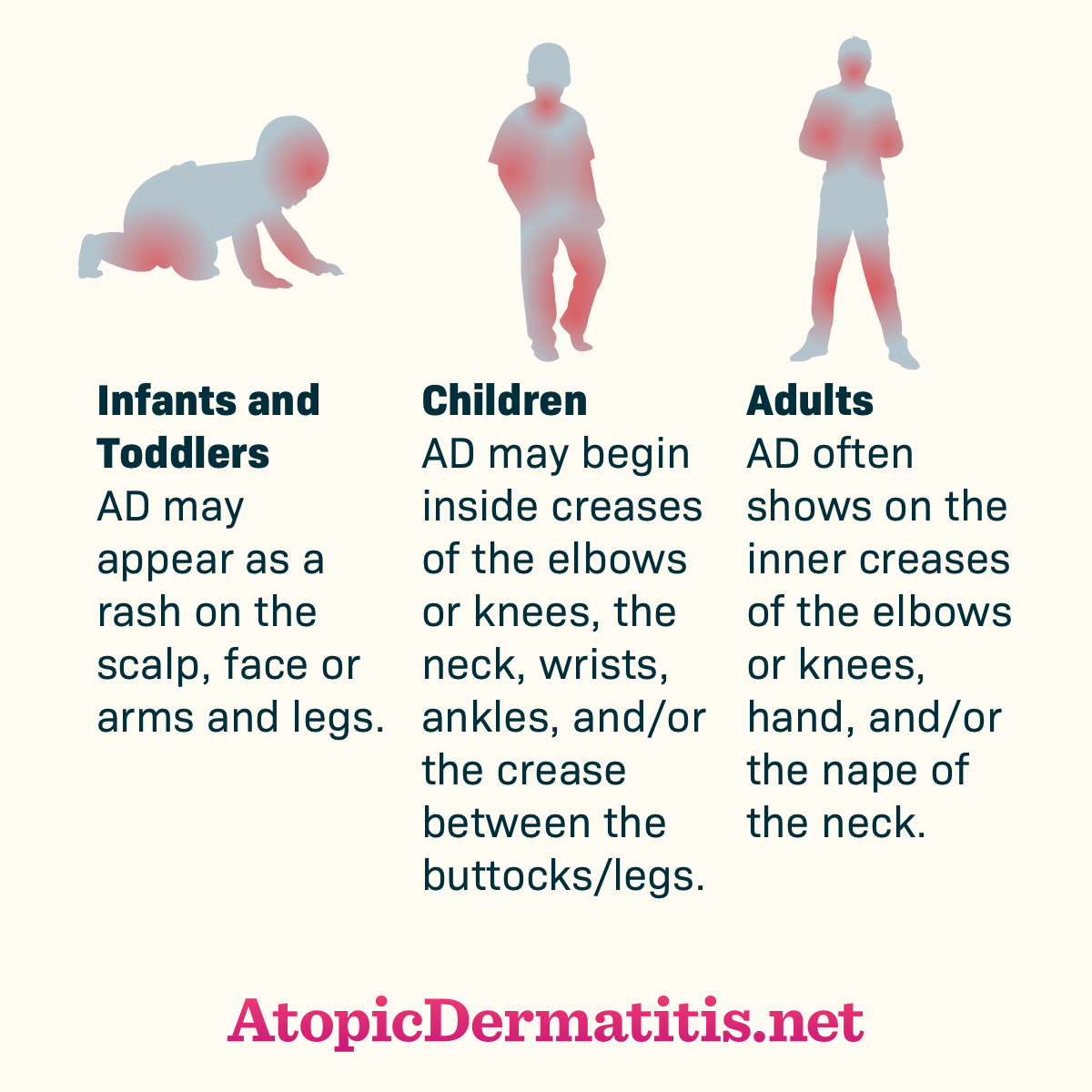

AD’s course is often punctuated by periods of exacerbations (flares), and periods of remission of various lengths.12 AD’s presentation varies depending on the patient’s age (see Figure 1) with most cases starting in early childhood.5 In infants, symptoms typically present early in life. Infants most often present with an erythematous, papular skin rash on the cheeks and chin, which can progress to red, scaling, oozing skin. The rash’s distribution changes as infants become more mobile (i.e., involvement of lower legs once crawling starts). Approximately 60% of patients with the disease present by age 1 year, and by age 5, about 90% of affected children are diagnosed.13 For many children, AD spontaneously resolves before adulthood, but some patients continue to have dermatitis into adulthood.3

Figure 1. Atopic Dermatitis Across the Lifespan

Retreived from https://atopicdermatitis.net/across-lifespan/. Used with permission from Health Union, LLC. (2017) Atopic Dermatitis Across the Lifespan [online image].

Rashes associated with AD are also itchy, and pruritis is AD’s hallmark. In fact, AD has been called “the itch that rashes.”14,15 Older children and adults often have areas of lichenification (thickened, leathery skin) as a result of repeated scratching. In adults, the rash is often more diffuse, with the face most commonly involved. The worldwide lifetime prevalence of AD in developed countries ranges from 10% to 20%.13 A 2010 nationwide survey estimated AD’s prevalence among American adults at 10.2%.16

Pathophysiology

AD’s pathogenesis is multifactored. Researchers believe that environmental, genetic, and immunologic factors may disrupt skin barrier function and dysregulate the immune system. Genetic and immunologic factors are closely related.

On a cellular level, infiltration of T cells and monocytes causes allergic sensitization and chronic inflammation. Furthermore, the ability of CD4+ T cells to recognize non-self and inform adaptive immune responses is impaired in patients with AD.17 Genetics clearly contribute.3 If both parents have a history of AD, their offspring have a greater than 80% chance of developing AD. Maternal history seems to contribute more heavily than paternal history. Researchers now believe that this genetic component involves mutations leading to alterations in the skin barrier. For example, filaggrin is an epidermal protein that maintains and hydrates the skin barrier. Research has identified several loss-of-function mutations in filaggrin that disrupt its normal processes. This changes skin pH, promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, and may allow unfettered growth of Staphylococcus aureus.17

In addition to genetic factors, a history of food allergy, asthma, or allergic rhinitis—all considered atopic disease—is a strong risk factor. Clinical progression from one atopic disease to another is called “atopic march.” Researchers have not determined how these atopic diseases are associated.18

Researchers also believe that environmental factors contribute to AD’s complex pathogenesis. Higher latitudes, colder temperatures, and low ultraviolet (UV) light exposure have been associated with increased AD symptoms.19 AD is diagnosed more often in children residing in urban areas and in areas with high levels pollution. In some patients, specific foods can trigger flares, but research indicates early introduction of certain foods in infants neither increases nor decreases risk of AD.18

Disease Burden and Comorbidities

Most common non-malignant dermatological disorders aren’t life threatening, but they create substantial health burden and decrease quality of life for patients and their families.20 AD creates psychological, social, and financial consequences for patients, and society bears some of the burden.

For patients, AD can be disfiguring, leading to anxiety, depression, humiliation, and embarrassment. For children, it may mean social isolation or missed days at school. Children struggle with disease-imposed limitations on outdoor play, swimming activities, and baths and may have difficulty finding friends. They may become irritable, hyperactive, frustrated, or attention-seeking. Parents also indicate that they spend 2 to 3 hours daily on treatments, and the arduous treatment regimens interfere with vacations, work, and personal pursuits. Parents also report difficulty finding suitable childcare.21,22 AD strains relationships in the family and is associated with significant out of pocket expense.22

Some adults with AD feel that the disease narrows their career choices, and others say it impedes career progression. In adults, work exposures to water, chemicals, or other irritant substances, can aggravate or exacerbate AD. Absenteeism or presenteeism (reduced productivity) can become a problem.20,23-25

Most patients with AD indicate that the most troubling symptom is itching, and the itching cascades into sleep disturbance. Up to 60% of children with eczema experience sleep disturbances, and it escalates during flares. Readers may well imagine that when children cannot sleep, the entire household is often disturbed.18 In addition to itch, adults indicate that xerosis (excessive dryness or scaling), and red, inflamed skin are also burdensome.26

In terms of comorbidities, a simple way to think about them is by classifying them as psychological (discussed above), infectious, and inflammatory, or immunologic.27 Researchers have proposed that AD’s inflammatory processes act in concert with inflammation in other organs and systems. Obesity, various cardiometabolic comorbid conditions, and AD are often comorbid, especially when the AD is moderate-to-severe or active over long durations. Some researchers suggest that chronic inflammation with differentiation toward type 2 helper T cell patterns and the long-term use of immunosuppressants elevate risk for comorbidities, especially autoimmune diseases.28,29

Clinical Presentation and Disease Severity Classification

Although several guidelines are available, most clinicians defer to the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines. Clinicians diagnosis AD after making a clinical assessment.18 The guidelines recommend including the following in each assessment:

- degree of pruritus

- eczema locations with typical morphology and patterns

- xerosis (dry skin)

- onset age

- history of personal or family atopy

- exclusion of other similar dermatologic conditions

Clinicians often assess AD’s using 1 of 3 tools: SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), or Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). SCORAD incorporates objective physician estimates of extent and severity and subjective patient assessment of itch and sleep loss; a score of more than 50 indicates severe disease, and a score of less than 25 indicates mild disease. EASI uses only objective physician estimates of disease extent and severity. POEM is a 7-question tool to gauge symptoms and their frequency to measure severity from the patient’s perspective.18

MINI-CASE: Oliver is a 4 month-old male recently diagnosed with AD. His mom tells you that he has a SCORAD score of 23, and asks what that means. After you explain that this means his AD is mild, she asks what options are available for such a young child. What can you recommend?

INITIAL THERAPY

Guidelines have identified 4 treatment goals for AD5:

- Provide symptomatic relief

- Control AD manifestations

- Minimize triggers or predisposing factors

- Prevent future exacerbations

As patients age and their life circumstances change, their symptoms will also change. One thing will remain consistent regardless of their age or skin condition; the need to take good care of their skin and moisturize appropriately.

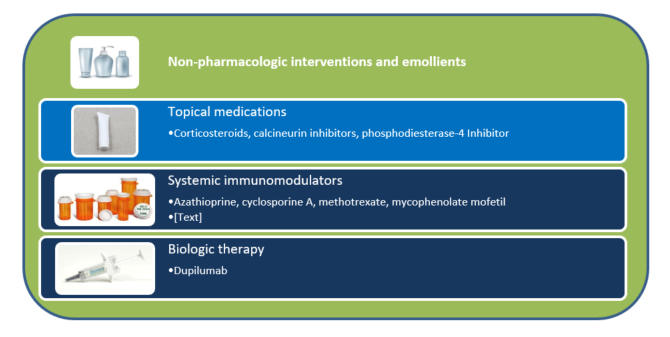

The basic approach to treating AD is a stepwise sequencing of topical medications followed by the use of systemic drugs and biologics (see Figure 2). Providers individualize regimens with consideration of disease severity, patient response, and tolerance.3,30 Many patients can manage mild AD with non-pharmacologic therapy. As AD’s severity increases, patients may need topical therapy with 1 or more drugs. Once AD reaches the moderate-to-severe level, clinicians and patients need to weigh the benefits and risks of systemic therapy alone (but usually in combination with topical treatments). Again, non-pharmacologic interventions and emollients will be the order of the day regardless of the patient’s age, disease severity, or status (stable or in a flare).

Figure 2. Atopic Dermatitis Treatment Overview

Non-Pharmacologic Management

Non-pharmacologic management of AD usually refers to bathing and moisturization. Bathing removes crusts and minimizes bacterial contamination. However, bathing in high-pressure showers or hot water, using drying detergents or soaps, or toweling off too vigorously can aggravate AD. Various guidelines recommend different bathing frequencies. Most dermatologists recommend bathing at most once daily with tepid water and gentle cleansers.31 Pharmacists should help patients identify low-irritant cleansers, which are have a low pH and are free of soap. They are also called Syndets (synthetic detergents). Patient also need to be aware of other interventions that may be useful or a waste of time or money (see Table 1).11,31-35

| Table 1. Topics of Interest to Patients and What the Evidence Says11,31-35 |

| Patients may ask about: |

The evidence indicates: |

| Antibiotics |

Antibiotics have no effect on stable disease in the absence of infection. |

| Antihistamines |

Short-term, intermittent use of sedating antihistamines may help patients who lose sleep because of itching, but should not be substituted for management of AD with topical therapies. |

| Evening primrose oil |

Some reports of dose-dependent benefit; conflicting results. |

| Probiotics |

Bacterial products may stimulate an immune response of the Th 1 series instead of Th 2 and may inhibit allergic IgE antibody production. Some report limited benefit in preventive and therapeutic roles. |

| Vinegar |

May be antibacterial. Add one cup to one pint of vinegar to the bath or use as a wet dressing |

It’s critical to emphasize that emollients prevent and treat flares and will be needed indefinitely. Patients with AD need to moisturize immediately after bathing and multiple times as needed during the day. Emollients contain oils and water in varying proportions; they rehydrate the skin in different degrees to prevent water loss through evaporation, which soothes and relieves pruritis25,36,37:

- Gels are transparent preparations containing cellulose ethers or carbomers in water or a water-alcohol mixture; they can be drying but are often preferable in hairy areas.

- Lotions are mixtures of water and oil (with more water than oil), spread easily and absorb well making them easy to use on hairy areas, but less effective moisturizers than creams or ointments.

- Creams are emulsions of approximately half water and half oil and are useful when lesions are weeping.

- Ointments are semisolids with the highest oil content, making them best to moisturize dry, thickened skin.

Patient preference for a product’s composition, absorption quality, and feel drive the choice of emollient, and pharmacists need to keep this in mind: patients will not use products they find pharmaceutically inelegant.

Components of some formulations—usually additives—can cause skin sensitivity. (note that ointments have no preservatives, so they are less likely to cause sensitivity.) Patients often find that switching to another product or formulation helps. Some products, usually those that are more occlusive, can cause folliculitis (inflammation and infection of hair follicles).17 Many patients use multiple topical products, and pharmacists should advise them to allow each product to dry before applying the next, which can take up to 30 minutes. Although research has not found that application order influences treatment outcomes, in general most dermatologists recommend applying medicated products before cosmetics and thinnest products before thickest (because the thinnest products dry more quickly).38

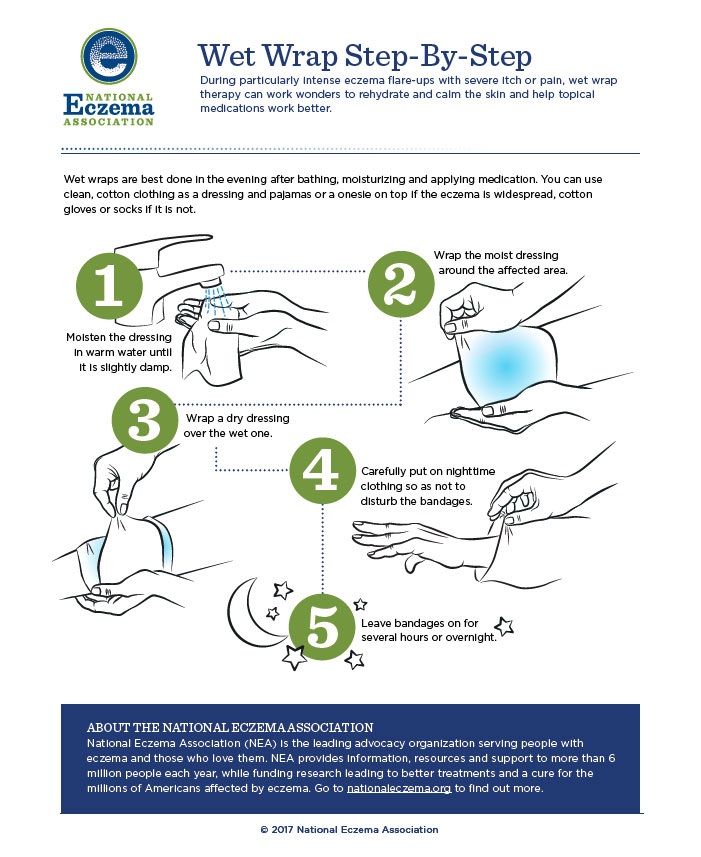

Wet Wrap Therapy (WWT)

For significant flares or unmanageable disease wet wrap therapy (WWT; applying a topical product then covering it with a wet layer of bandages, gauze, or a cotton suit, followed by a dry outside layer) helps. WWT occludes topical medication and increases its penetration, helping severe disease. It also decreases skin’s water loss and provides a physical barrier against scratching (thus preventing excoriation). Patients can wear WWT for several hours, up to 24 hours at a time, and repeat daily for up to 2 weeks depending on patient tolerance. Applying topical corticosteroids under WWT is more effective than moisturizers alone, but caution is important. As absorption of topical steroids increases, so does the risk of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression. Limiting to once daily application or diluting the steroid to 5% to 10% of its original strength reduces risk.30 Figure 3 describes the WWT process.

Figure 3. WWT Process

MINI-CASE: Gary, a 72-year-old man with moderate eczema on his hands comes to your pharmacy seeking advice. He loves to cook, but after working at a community spaghetti dinner recently, his AD worsened. He thinks that all the dishwashing aggravated it. He needs a more aggressive emollient and wants to know if he should start using his as-needed fluocinolone cream. What are the most important counseling points for Gary?

MANAGEMENT OF MODERATE-TO-SEVERE AD

When non-pharmacologic treatments fail to provide sufficient relief, the guidelines recommend stepping therapy up by adding active prescription medications. Pharmacologic management starts with topical corticosteroids (TCSs).18 Ample evidence indicates that TCSs are safe and effective, making them first-line for AD flares. Next, topical anti-inflammatory calcineurin inhibitors (TCNIs) are second-line options for most patients if TCSs fail to provide relief. Topical therapy is most effective when prescribers ensure patients receive a sufficient strength and dose, and apply it correctly.39

Topical Corticosteroids (TCSs)

Corticosteroids interfere with antigen processing, suppress the release of proinflammatory cytokines, and reduce inflammation.18 They have been and remain the foundation of topical anti-inflammatory therapy in AD to treat and prevent flares. They decrease acute and chronic signs of AD. Table 2 lists the available TCSs and their dosage formulations and potencies.40 There is limited evidence to recommend optimal potency, dosage form, frequency, and dose of TCSs. In most cases, patients will have definite preferences based on previous experience that can help clinicians prescribe the best drug, dosage form, and dose.

| Table 2. Relative Potencies of Topical Corticosteroids8,40 |

| Potency |

Topical Corticosteroids |

| Very High |

Augmented betamethasone dipropionate ointment 0.05%

Clobetasol propionate cream, foam, ointment 0.05%

Diflorasone diacetate ointment 0.05%

Halobetasol propionate cream, ointment 0.05% |

| High |

Amcinonide cream, lotion, ointment 0.1%

Augmented betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%

Betamethasone dipropionate cream, foam, ointment, solution 0.05%

Desoximetasone cream, ointment 0.25%

Desoximetasone gel 0.05%

Diflorasone diacetate cream 0.05%

Fluocinonide cream, gel, ointment, solution 0.05%

Halcinonide cream, ointment 0.1%

Mometasone furoate ointment 0.1%

Triamcinolone acetonide cream, ointment 0.5% |

| Medium |

Betamethasone valerate cream, foam, lotion, ointment 0.1%

Clocortolone pivalate cream 0.1%

Desoximetasone cream 0.05%

Fluocinolone acetonide cream, ointment 0.025%

Flurandrenolide cream, ointment 0.05%

Fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%

Fluticasone propionate ointment 0.005%

Mometasone furoate cream 0.1%

Triamcinolone acetonide cream, ointment 0.1% |

| Lower-Medium |

Hydrocortisone butyrate cream, ointment, solution 0.1%

Hydrocortisone probutate cream 0.1%

Hydrocortisone valerate cream, ointment 0.2%

Prednicarbate cream 0.1% |

| Low |

Alclometasone dipropionate cream, ointment 0.05%

Desonide cream, gel, foam, ointment 0.05%

Fluocinolone acetonide cream, solution 0.01% |

| Lowest |

Dexamethasone cream 0.1%

Hydrocortisone cream, lotion, ointment, solution 0.25%, 0.5%, 1%

Hydrocortisone acetate cream, ointment, 0.5% to 1% |

Usually, patients will use low-potency TCSs twice daily 2 to 3 times weekly for maintenance therapy and medium-to-high potency TCSs twice daily every day when they experience acute flares.41 Some patients use low-potency products for all flares and increase the potency if the initial treatment fails. Although the guidelines recommend applying most TCSs twice daily, some data suggests once daily application may be appropriate.18 Most insurers will pay for approximately 15 grams in infants, 30 grams in children, and up to 60 to 90 grams in adolescents and adults every month.39

To determine when to discontinue TCSs prescribed for a flare, clinicians need to monitor the patient’s pruritis. If a patient continues to have itching, he or she should continue to use the TCS. After resolution, many clinicians taper the TCS (although no definitive evidence indicates this is necessary). Applying low-potency TCSs once or twice weekly after the flare resolves can help reduce recurrence.18,39 Studies of the most appropriate duration of preventive therapy are underway.

Before discussing adverse effects, it’s critical to address “steroid phobia.” Studies indicate that 40% of patients believe common myths about steroids and 80% avoid using them even when they are needed. A survey conducted in a pediatric outpatient dermatology clinic found that more than 40% of caregivers reported a fear of topical corticosteroids “often” or “always”; 41% applied topical corticosteroids only when AD worsened; and 30% requested a steroid-sparing alternative.42 Steroid phobia often leads to nonadherence and treatment failure. Pharmacists need to assure patients that risk of adverse effects is low, and excellent adherence can manage AD effectively.

Adverse effects associated with TCSs are generally dermatologic. Local adverse effects include cutaneous atrophy, erythema, and hypopigmentation. Experts advise caution when using potent TCSs on thin skin, such as the face, neck, and skin folds. In these areas, absorption is likely to be higher, increasing risk of skin atrophy. Small children have body surface areas that are proportionately larger than larger children and adults and are at increased risk of systemic absorption.39 Very rarely, patients of any age may develop systemic adrenal suppression after using very high-potency topical corticosteroids. Patients may also experience symptom exacerbation when they discontinue TCSs: the longer the duration of treatment, the more likely this is.43

Parents need good direction from health care providers so they are prepared to use TCS appropriately. This is especially important when using high-potency TCSs because TCS withdrawal (i.e., rosacea-like dermatitis, burning, and stinging) can occur when they stop the TCS.44 Explaining application using the Fingertip Unit (FTU) is helpful. One FTU of a TCS will cover an area the size of 2 adult palms or 2% of body surface. To measure a FTU from a tube with a 5 mm nozzle, patients should express 0.5 grams of cream or ointment from the tube. That is the amount that reaches from an adult’s distal interphalangeal joint (the first joint in from the tip) to the fingertip.39

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors (TCNIs)

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 2 TCNIs (tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream) for short-term and long-term use in adults and children who have AD. TCNIs suppress T-cell and mast cell activation and block production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.18

The guidelines recommend TCNIs as second-line agents when TCSs are ineffective. However, patients who have flares in sensitive areas (e.g. the face or skin folds), have used TCS for long durations, or who experience TCS-induced skin atrophy may benefit from TCNIs.18

Tacrolimus comes in 0.03% and 0.1% strengths – the 0.1% strength is comparable to mid-potency TCSs but FDA has only approved the 0.03% strength in children aged 2 to 15 years. Pimecrolimus 0.1% is considered less efficacious than mid-to-high potency TCSs. During acute flares, the guidelines recommend twice-daily application. After the flare resolves, applying the TCNI 2 to 3 times weekly reduces relapse rates and can be cost-effective.45 TCNIs’ adverse effects include burning and stinging at the application site. Pharmacists need to tell patients that these adverse effects decrease with continued use and they should continue to use the TCNI.18

Some patients on TCNIs have experienced viral cutaneous reactions, but epidemiologists have not identified a definitive relationship between these drugs and this reaction.39 All TCNIs are labeled with a boxed warning indicating a risk of malignancy, but this association has not been validated.39 A very recent study looked at tacrolimus use in almost 8000 patients, and found no increased risk of cancer in children with AD.46As a precaution, patients should use sunscreens that provide ultraviolet (UV) protection while on TCNIs. Discussing the boxed warning transparently and using evidence may lead to improved adherence.

Topical Phosphodiesterase (PDE) Inhibitor

Crisaborole is a phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor that downregulates nuclear factor-kB and activated T-cell signaling pathways to suppress cytokine release.52 Early studies of this drug included children and adolescents,47-50 leading to initial approval in children age 2 and older initially for mild-to-moderate AD. (In March of 2020, FDA approved crisaborole ointment for infants aged 3 months or older based on data from an unpublished phase 4 trial.51) Its approval was based on 2 randomized placebo-controlled trials that enrolled 764 patients between them. Patients in the crisaborole arm were more likely to achieve reduction in disease severity or have clear or almost clear skin at day 29 than patients in the placebo arm. Patients in the treatment arm also reported earlier resolution of itching.52 The most common adverse effects (reported as infrequent and mild-to-moderate in severity) included application site burning or stinging. A subsequent study (n = 517) looked at long-term safety in an open label 48-week multicenter study in a similar population; it did not look at efficacy. The researchers found a low frequency of treatment-related AEs (10.2%) with dermatitis, application site pain, and application site infection reported most often.41

Researchers conducted a pooled post hoc analysis by race and ethnicity of these pivotal trials and performed a safety extension trial in 2019 because AD is prevalent in Black/African American, Asian, and Hispanic populations.53 Their results were similar to those reported above. At day 29, more crisaborole- than vehicle-treated patients who were classified as white, nonwhite, Hispanic/Latino, and not Hispanic/Latino achieved clear or almost clear skin. Study participants reported improved AD signs/symptoms and quality of life. Adverse event rates were similar to those identified in the pivotal studies.53

Patients apply crisaborole ointment twice daily. Crisaborole has not been studied in head-to-head trials of TCSs or TCNIs.

Phototherapy

UV therapy is a second-line therapy for patients who have chronic, pruritic AD that responds positively to sunlight.39 UV radiation stimulates apoptosis (programmed cell death) of inflammatory cells.54 For safety reasons, narrowband UVB is preferred over broadband UVB, and medium-dose UVA1 is similar in efficacy to narrowband UVB. UV therapy may put patients at risk for premature skin aging and skin cancer; however, this is more likely when used in combination with photosensitizing medications. Contraindications to therapy include inherited and acquired disorders that may be worsened by UV light, such as lupus erythematous.55 During phototherapy, patients should avoid immunosuppressants, but continue topical steroids and emollients to prevent potential flares.

MINI-CASE: Jack is a 35-year-old male who has struggled with AD management for many years. He has tried 2 high-potency TCS and a TCNI for his most recent outbreak. His SCORAD index is higher than 50, indicating severe disease. His dermatologist calls your pharmacy seeking advice about available systemic options. What drugs or biologics are suitable for Jack?

Systemic Immunomodulating Drugs

When patients experiencing moderate-to-severe AD are refractory to topical therapies, clinicians often consider systemic immunosuppression in their oral forms. Clinicians prescribe 4 systemic immunomodulating drugs (small molecules as opposed to biologics, discussed below), and pharmacists should note 3 points: all of them are used off-label, elevate risk for infection, and may also increase risk of malignancy.

Cyclosporine A (CsA)

Cyclosporine A (CsA) is an oral calcineurin inhibitor that inhibits proinflammatory cytokine transcription to inhibit T cell activation.56 A pooled meta-analysis assessed CsA’s effectiveness in severe AD and found a relative effectiveness of 55% after 6 to 8 weeks of therapy. The response was dose-related with doses of 4 mg/kg or higher associated with greater responses. CsA’s adverse effect profile limits dose escalation; as the dose of CsA increases, so does the likelihood of adverse effects.57 Adverse effects are also more likely to occur in patients aged 45 years or older. Certain adverse effects are linked to drug discontinuation, especially elevated serum creatinine levels, hypertension, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

CsA can cause photosensitivity. Pharmacists should counsel patients about the potential for nephrotoxicity and instruct patients to avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Prescribers should schedule routine serum creatinine levels to monitor renal dysfunction. Various brand names, Neoral®/Gengraf® (CsA modified) and Sandiummune® (CsA non-modified), are not interchangeable due to differences in bioavailability; this is a Pro Tip for pharmacists. Patients will ideally receive 2 years of treatment, but disease control, adverse effects, and ineffectiveness may result in early discontinuation.39,57 Many patients experience prompt relapse upon discontinuation.

Azathioprine (AZA)

For patients with AD who cannot tolerate or do not respond to CsA, azathioprine (AZA) is an option.57 AZA inhibits purine synthesis and consequently DNA and RNA production for synthesis of white blood cells, thus causing immunosuppression.7,58 Randomized, controlled studies in adults demonstrate AZA’s efficacy is better than placebo and comparable to methotrexate (MTX). Response may take 4 or more weeks.59Although patients report improvement, here too, azathioprine’s adverse effect profile (e.g. gastrointestinal disturbances, leukopenia, and hepatotoxicity) limits its utility and often leads to drug discontinuation.60 Dividing doses or administering doses with food may minimize gastrointestinal adverse effects.61

Concurrent phototherapy increases risk of DNA damage and carcinogenesis and is contraindicated. Patients should limit UV exposure, and use a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 of higher and other appropriate sun protection. Myelotoxicity has been reported, especially in patients with thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) polymorphism. Clinicians should consider dose reductions in patients with reduced TPMT activity.61

Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF)

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) blocks inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase to cause a relatively selective inhibition of DNA replication in T cells and B cells. Little prospective evidence supports its efficacy in AD, but it is employed.58 MMF’s most common adverse effects are nausea and diarrhea. Myelosuppression, hypertension, and infection are also possible, and pharmacists should heighten vigilance in pediatric patients.62 Dosing may need to be adjusted for neutropenia or anemia.

MMF is teratogenic; women must discontinue MMF at least 6 weeks before a planned pregnancy. Similar to CsA, mycophenolate is available in 2 formulations that are not interchangeable: mycophenolate mofetil (MMF, CellCept®) and mycophenolate sodium enteric coated (Myfortic®). These products have different absorption rates and require different dosing.

Methotrexate (MTX)

MTX binds irreversibly to inhibit dihydrofolate reductase, but its mechanism in AD is unclear. It may interfere with T-cell activation to dampen immune function and inflammation. MTX is used in patients with adult-onset AD; however, literature supporting its use in pediatric disease is limited.2 One pediatric, prospective, multicenter study compared MTX to CsA and found no statistically significant difference in efficacy between the 2 groups at 12 weeks.63 Due to its mechanism of action, folic acid supplementation may be required to reduce the risk of adverse effects. MTX’s most common adverse effects include nausea, anemia, and fatigue. Bone marrow suppression, aplastic anemia, and gastrointestinal toxicity have been reported with concomitant administration of some NSAIDs. With prolonged use, hepatotoxicity may occur, and pneumonitis may occur at any point during therapy. MTX, like MMF, is teratogenic and contraindicated in pregnancy.58 Unlike the other immunosuppressive agents, MTX is dosed weekly rather than daily. Ensuring appropriate prescribing and administration is an important role for pharmacists.

MINI-CASE: Jack’s dermatologist decides to start him on oral methotrexate. He comes to your pharmacy to pick up his prescription. What are the most important counseling points for Jack, and what should you talk about in addition to MTX’s dosing and adverse effects?

A BIOLOGIC AGENT

Biologic therapies target specific inflammatory cells and cell mediators to reduce inflammation. FDA approved the biologic agent, dupilumab, for AD in March 2017. It is now approved for people who are at least 6 years old with moderate-to-severe AD that is poorly controlled with prescription topicals, or who cannot use topical therapies.64 It is also approved for asthma in adolescents and adults and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis in adults.

Dupilumab

Dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody, targets pathways that are key mediators in AD.64,65 Inflammation is an important component in the pathogenesis of the 3 conditions for which dupilumab is approved. Blocking interleukin (IL)-4Rα inhibits the IL-4 and IL-13 cytokine-induced inflammatory cascade, including the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, nitric oxide, and IgE.

Four phase 3 clinical trials demonstrated dupilumab’s efficacy and safety, including 1 trial that assessed patients over 12 months.65 In this study, all subjects used concomitant TCS with or without topical TCNI. Participants tapered, stopped, or started topical products based on disease activity. The researchers observed a statistically significant improvement in symptoms in the dupilumab arm compared to placebo. No significant laboratory abnormalities were noted. The most common adverse effects were injection site reactions and conjunctivitis.65

Some readers may wonder why dupilumab is associated with conjunctivitis. Patients with AD have a higher prevalence of ocular comorbidities than that found in the overall population.66 Barrier dysfunction in skin—and in the eyes—is AD’s hallmark. Researchers have proposed many theories including66

- alterations in cytokine activity

- higher levels of Demodex mites

- elevated OX40 ligand activity

- eosinophilia

- disruption of an immune‐mediated response of conjunctival‐associated lymphoid tissue

- decreased IL‐13‐related mucus production and IL‐13‐related scarcity of conjunctival goblet cell

Dupilumab dosing is described in Table 3.64 Clinical trials are evaluating dupilumab in pediatric patients age 6 months to 6 years, ages 6 to 18, and ages 6–12 years with co-administration of TCS.

| Table 3. Dupilumab Dosing in Pediatric Patients64 |

| Body Weight |

Initial Dose |

Subsequent Doses |

| 15 to less than 30 kg |

600 mg (two 300 mg injections) |

300 mg every 4 weeks |

| 30 to less than 60 kg |

400 mg (two 200 mg injections) |

200 mg every 2 weeks |

| 60 kg or more |

600 mg (two 300 mg injections) |

300 mg every 2 weeks |

The current recommendation for place in therapy is following optimization of topical therapy and after treatment failure of 1 or more oral immunosuppressive drugs.67 Importantly, dupilumab’s safety profile offers an improvement from previously used, off-label systemic immunomodulators.

MINI-CASE: Jacie is a 22-year-old female with poorly-controlled AD, a problem she has experienced since infancy. Her physician has suggested dupilumab, but Jacie is skeptical about its ability to address her symptoms and the need to self-inject. How can you employ motivational interviewing to help her move forward?

ADHERENCE ISSUES AND POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

Patients who have chronic skin conditions are notoriously nonadherent to treatment. Patients with AD have numerous complaints about treatment that contribute to poor long-term outcomes.68 This includes the time-consuming need to moisturize; the pharmaceutical elegance of the products and patient perceptions of their feel when applied; or frustrations with medication efficacy. Steroid phobia is an additional concern. Studies indicate that up to 80% of patients believe common myths about steroids and avoid using them even when they are needed.69 Steroid phobia often leads to nonadherence and treatment failure. High cost and lack of long-term safety data can limit dupilumab use. Patients may be hesitant to self-inject. Pharmacists can address this fear by counseling on proper subcutaneous injection technique as well as the potential benefit of medication adherence.

As with any chronic disease, patient attitude and behavior are significant factors in overall treatment success. Clinicians who practice in asthma management have made great strides by publicizing the need for every patient to have an asthma action plan.70 Patients with AD have a similar need. Each AD patient needs an individualized regimen or action plan that considers the patient's age, the stage and variety of lesions present, the sites and extent of involvement, the presence of infection, and the previous response to treatment.71,72,73 Pharmacists can provide accurate, realistic information about bathing, proper moisturizing, and prescription AD treatments and contribute to the AD action plan.

Use motivational interviewing (and open-ended questions) to improve adherence to both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment options.74,75 Listen to patients’ thoughts about change, and what they think change will require. Reflect your understanding (“I know that the bathing process can be time-consuming.”) Identify missing or incorrect information, but don’t do it in a confrontational or scolding manner. Ask if you can address an issue directly, and do so only if the patient agrees. (“May I say something about topical corticosteroids that I learned in a class recently?”) Invite patients to reconsider, and summarize and reiterate next steps. (“You said that constant itching at night is very disruptive, and we talked about 3 things that might help— moisturizing with a heavier, scent-free cream, using your topical corticosteroid more consistently, and asking your dermatologist if you might be a good candidate for dupilumab. Which of those approaches might you be able to try before giving up?”)76,77

CONCLUSION

The treatment of AD should follow a stepwise approach that is individualized to a patient’s disease severity. While mild disease may only require as-needed use of topical corticosteroids, patients with moderate disease require regular use of topical anti-inflammatory agents such as topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, or crisaborole. Patients with severe or nonresponsive disease should be considered for evaluation by a specialist for potential systemic treatment, such as dupilumab or other off-label systemic immunosuppressants.

References

- Bickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, et al. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(3):490–500.

- Adamson AS. The economics burden of atopic dermatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1027:79‐92. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64804-0

- Lawley LP, McCall CO, Lawley TJ. Eczema, psoriasis, cutaneous infections, acne, and other common skin disorders. In: Jameson J, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Loscalzo J. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 20e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; . http://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2129§ionid=192013524. Accessed June 7, 2020.

- Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1109-1122.

- Law RM, Kwa PG. Atopic dermatitis. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 10th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2017.

- Willemsen MG, van Valburg RW, Dirven-Meijer PC, et al. Determining the severity of atopic dermatitis in children presenting in general practice: an easy and fast method. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009;2009:357046.

- Nygaard U, Deleuran M, Vestergaard C. Emerging treatment options in atopic dermatitis: topical therapies. Dermatology. 2017;233(5):333-343.

- Draelos ZD, Feldman SR, Berman B, et al. Tolerability of topical treatments for atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9(1):71-102.

- Slater NA, Morrell DS. Systemic therapy of childhood atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33(3):289-299.

- Siegfried EC, Jaworski JC, Kaiser JD, et al. Systematic review of published trials: long-term safety of topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:75.

- Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327-349.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):283-289.

- Williams H, Stewart A, von Mutius E, et al. Is eczema really on the increase worldwide? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(4):947-954.

- Scrubbing In. Eczema—“The itch that rashes.” Accessed at https://scrubbing.in/eczema-the-itch-that-rashes/, June 12, 2020.

- Consultant 360. The itch that rashes. Accessed at https://www.consultant360.com/articles/itch-rashes, June 12, 2020.

- Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132-1138.

- Lyons JJ, Milner JD, Stone KD. Atopic Dermatitis in Children: Clinical Features, Pathophysiology and Treatment. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35(1):161-183.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338-351.

- Flohr, C, Mann J. New approaches to the prevention of childhood atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2014;69(1):56-61.

- Drucker AM, Wang AR, Li WQ, et al. The burden of atopic dermatitis: summary of a report for the National Eczema Association. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(1): 26-30.

- Su JC, Kemp AS, Varigos GA, et al. Atopic eczema: its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76: 159–162.

- Chamlin SL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Chren MM. Effects of atopic dermatitis on young American children and their families. Pediatrics. 2004;114:607e11.

- Dirschka T, Micali G, Papadopoulos L, Tan J, Layton A, Moore S. Perceptions on the psychological impact of facial erythema associated with rosacea: results of international survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5(2):117-127. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0077-2

- Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JY. Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practice. Dermatol Online. 2014;20(8). pii:13030/qt48r4w8h2.

- Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: A population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340-347.

- Carrascosa JM, Morillas V. Comorbidities in atopic dermatitis: an update and review of controversies [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 10]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;S0001-7310(20)30136-8. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2020.04.009

- Andersen YMF, Egeberg A, Skov L, Thyssen JP. Comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: beyond rhinitis and asthma. Current Dermatology Reports. 2017;6(1):35-41.

- Gilaberte Y, Pérez-Gilaberte JB, Poblador-Plou B, Bliek-Bueno K, Gimeno-Miguel A, Prados-Torres A. Prevalence and Comorbidity of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: A Large-Scale Population Study Based on Real-World Data. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):E1632. Published 2020 May 28. doi:10.3390/jcm9061632

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116‐132. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.023

- Cardona ID, Kempe E, Hatzenbeuhler JR, et al. Bathing frequency recommendations for children with atopic dermatitis: results of three observational pilot surveys. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(4):e194-e196.

- Asai Y, Tan J, Baibergenova A, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for rosacea. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(5):432-445. doi:10.1177/1203475416650427

- George SM, Karanovic S, Harrison DA, et al. Interventions to reduce Staphylococcus aureus in the management of eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2019(10):CD003871.

- Chung BY, Kim JH, Cho SI, et al. Dose-dependent effects of evening primrose oil in children and adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(3):285-291. doi:10.5021/ad.2013.25.3.285

- Makrgeorgou A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall FJ, et al. Probiotics for treating eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11(11):CD006135. Published 2018 Nov 21. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006135.pub3

- Silverberg JI, Nelson DB, Yosipovitch G. Addressing treatment challenges in atopic dermatitis with novel topical therapies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(6):568-576.

- Peacock, S. Use of emollients in the management of atopic eczema. Br J Community Nurs. 2016;21(2):76-80.

- Ng SY, Begum S, Chong SY. Does order of application of emollient and topical corticosteroids make a difference in the severity of atopic eczema in children? Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(2):160-164.

- Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657-682.

- Topical Corticosteroids. Lexi-Drugs. Lexicomp. Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. Riverwoods, IL. Accessed at: http://online.lexi.com., November 11, 2018.

- Eichenfield LF, Call RS, Forsha DW, et al. Long-term safety of crisaborole ointment 2% in children and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):641-649.

- Hon KL, Tsang YC, Pong NH, et al. Correlations among steroid fear, acceptability, usage frequency, quality of life and disease severity in childhood eczema. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(5):418-425.

- van Velsen SG, De Roos MP, Haeck IM, et al. The potency of clobetasol propionate: serum levels of clobetasol propionate and adrenal function during therapy with 0.05% clobetasol propionate in patients with severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:16-20.

- Takahashi-Ando N, Jones MA, Fujisawa S, Rokuro H. Patient-reported outcomes after discontinuation of long-term topical corticosteroids treatment for atopic dermatitis: a targeted cross-sectional survey. Drug Health Patient Saf. 2015;7:57-62.

- Breneman D, Fleischer AB Jr, Abramovits W, et al. Intermittent therapy for flare prevention and long-term disease control in stabilized atopic dermatitis a randomized comparison of 3-times-weekly applications of tacrolimus ointment versus vehicle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:990-999.

- Paller AS, Fölster-Holst R, Chen SC, et al. No evidence of increased cancer incidence in children using topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 1]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30498-9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.075

- Tom WL, Van Syoc M, Chanda S, Zane LT. Pharmacokinetic profile, safety, and tolerability of crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in adolescents with atopic dermatitis: an open-label phase 2a study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(2):150‐159. doi:10.1111/pde.12780

- Zane LT, Kircik L, Call R, et al. Crisaborole topical ointment, 2% in patients ages 2 to 17 years with atopic dermatitis: a phase 1b, open-label, maximal-use systemic exposure study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(4):380‐387.

- Stein Gold LF, Spelman L, Spellman MC, Hughes MH, Zane LT. A phase 2, randomized, controlled, dose-ranging study evaluating crisaborole topical ointment, 0.5% and 2% in adolescents with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14(12):1394‐1399.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults [published correction appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Apr;76(4):777]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):494‐503.e6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.046

- [No author.] U.S. FDA approves supplemental new drug application (snda) for expanded indication of EUCRISA® (crisaborole) ointment, 2%, in children as young as 3 months of age with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. March 24, 2020. Accessed at https://investors.pfizer.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2020/US-FDA-Approves-Supplemental-New-Drug-Application-sNDA-for-Expanded-Indication-of-EUCRISA-Crisaborole-Ointment-2-in-Children-as-Young-as-3-Months-of-Age-With-Mild-to-Moderate-Atopic-Dermatitis/default.aspx, June 7, 2020.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):494-503.e6.

- Callender VD, Alexis AF, Stein Gold LF, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, 2%, for the treatment of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis across racial and ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(5):711‐723. doi:10.1007/s40257-019-00450-w

- Brenninkmeijer EE, Legierse CM, Sillevis Smitt JH, et al. The course of life of patients with childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(1):14-22.

- Crall CS, Rork JF, Delano S, Huang JT. Phototherapy in children: considerations and indications. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(5):633-639.

- Schmitt J, Schmitt N, Meurer M. Cyclosporin in the treatment of patients with atopic eczema – a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(5):606-619.

- van der Schaft J, Politiek K, van den Reek JM, et al. Drug survival for ciclosporin A in a long-term daily practice cohort of adult patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1621-1627.

- Imuran (azathioprine) package insert. San Diego, CA: Prometheus Laboratories, Inc.: May 2011.

- Schmitt J, Abraham S, Trautmann F, et al. Usage and effectiveness of systemic treatments in adults with severe atopic eczema: First results of the German Atopic Eczema Registry TREATgermany. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15(1):49-59. doi:10.1111/ddg.12958

- Berth-Jones J, Takwale A, Tan E, et al. Azathioprine in severe adult atopic dermatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(2):324-330.

- Meggitt SJ, Gray JC, Reynolds NJ. Azathioprine dosed by thiopurine methyltransferase activity for moderate-to-severe atopic eczema: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:839-846.

- CELLCEPT (mycophenolate mofetil) prescribing information. South san Francisco, CA: Genentech USA,Inc.; December 2019.

- El-Khalawany MA, Hassan H, Shaaban D, et al. Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in children: a multicenter experience from Egypt. Eur J 2013;172(3):351-356.

- Dupixent (dupilumab) package insert. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; May 2020.

- Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287-2303.

- Treister AD, Kraff-Cooper C, Lio PA. Risk Factors for Dupilumab-Associated Conjunctivitis in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(10):1208-1211. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2690

- Ariëns LFM, Bakker DS, van der Schaft J, et al. Dupilumab in atopic dermatitis: rationale, latest evidence and place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9(9):159-170.

- Patel N, Feldman SR. Adherence in atopic dermatitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1027:139-159.

- Hon KL, Tsang YC, Pong NH, et al. Correlations among steroid fear, acceptability, usage frequency, quality of life and disease severity in childhood eczema. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(5):418-425.

- American Lung Association. Create an asthma action plan. Accessed at https://www.lung.org/lung-health-and-diseases/lung-disease-lookup/asthma/living-with-asthma/managing-asthma/create-an-asthma-action-plan.html, June 7, 2020.

- Levy ML. Developing an eczema action plan. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):659-661.

- O'Toole A, Thomas B, Thomas R. The care triangle: determining the gaps in the management of atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17(4):276-282.

- Snyder A, Farhangian M, Feldman SR. A review of patient adherence to topical therapies for treatment of atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2015;96(6):397-401.

- Wong ITY, Tsuyuki RT, Cresswell-Melville A, et al. Guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis (eczema) for pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2017;150(5):285-297.

- Pringle J, Coley KC. Improving medication adherence: a framework for community pharmacy-based interventions. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2015;4:175-183.

- Wibowo E, Wassersug RJ, Robinson JW, et al. An educational program to help patients manage androgen deprivation therapy side effects: feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes. Am J Mens Health. 2020;14(1):1557988319898991. doi: 10.1177/1557988319898991.

- Spencer JC, Wheeler SB. A systematic review of motivational interviewing interventions in cancer patients and survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2016l;99(7):1099-1105. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.02.003.

Back to Top