Expired activity

Please go to the PowerPak

homepage and select a course.

Pharmacists as Key Members of the HIV Prevention Team: Opportunities to Support PrEP and nPEP Efforts

Introduction

In February 2019, the United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) announced an initiative to end the HIV Epidemic in the United States with a goal of 90% reduction in new HIV infections within the next 10 years. (Fauci 2019) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will focus on high prevalence communities and provide funding to establish and expand programs for HIV diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and response to outbreaks. Prevention efforts will focus on proven interventions including syringe service programs and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), along with post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) which can often serve as a bridge to PrEP use. (CDC 2019)

Due to the combination of their training, experience educating patients, and their role as members of the healthcare team, pharmacists are well positioned to contribute in efforts to end the HIV epidemic by supporting the appropriate use of PrEP and nPEP. As noted in the 2016 guidelines issued by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, “HIV prevention requires an interdisciplinary approach involving pharmacists as active members of the healthcare team. Active pharmacist participation in prevention initiatives can help prevent transmission and reduce the rate of HIV infection. Pharmacists play a key role in HIV prevention through both pharmacologic and behavioral interventions.” (ASHP 2016) To fully embrace this role, it is essential that pharmacists continue to seek out education that improves their knowledge and competence/skills regarding PrEP and PEP, and how they can contribute to the interprofessional care team.

PrEP: A Tool for HIV Prevention

PrEP is the use of antiretrovirals (ARVs) in HIV negative persons prior to exposure to prevent HIV infection. PrEP with the oral combination tablet of emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) is highly effective at preventing new HIV infections in high risk individuals and was FDA approved for prevention (PrEP) in adults in 2012 and adolescents in 2018. A second combination tablet emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (FTC/TAF) was newly FDA approved In October 2019 to reduce the risk of HIV-1 for high risk adults and adolescents, excluding those at risk from receptive vaginal sex for whom effectiveness has not yet been established. Although CDC guidelines have recommended PrEP use in high-risk individuals since they were published in 2014, PrEP use in the US has remained low with less than 10% of the estimated 1.1 million persons at risk taking the preventative medication. (CDC 2019)

In June 2019, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) provided a grade A recommendation that clinicians should offer PrEP to persons at high risk of HIV acquisition. This strong recommendation not only reinforced the importance of effective HIV prevention, but will likely lead to expanded access to PrEP due to mandates in the Affordable Care Act surrounding coverage of preventative services. (Owens 2019)

Epidemiology

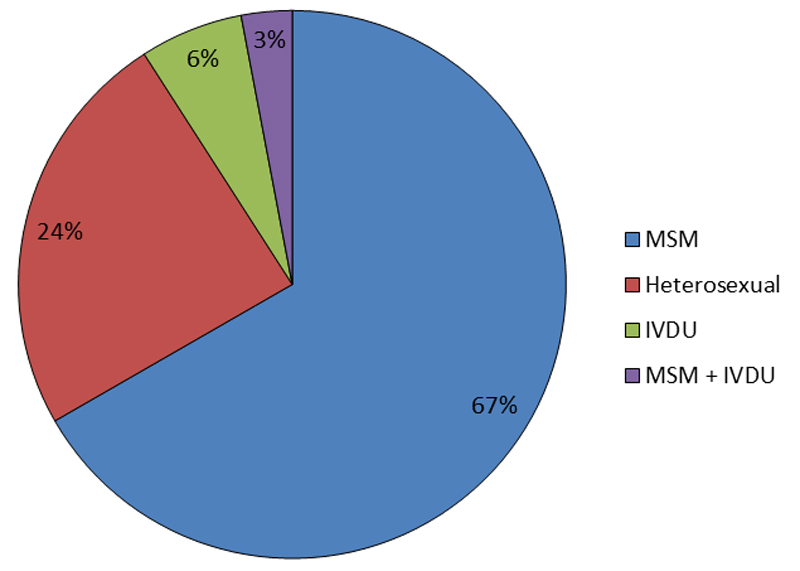

There are an estimated 1.1 million persons living with HIV in the United States in 2016 and over 38,000 new HIV diagnoses in 2017. Most new diagnoses were through male-to-male sexual contact and heterosexual contact followed by intravenous drug use (IVDU). (CDC 2017) (See Figure 1.) HIV diagnoses disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic Americans as well as transgender individuals. The lifetime risk of acquiring HIV in a Black MSM (men who have sex with men) is 1 in 2 and 1 in 4 for Hispanic MSM. This racial/ethnic disparity is also seen in women with the lifetime risk of acquiring HIV being 17 times higher in Black women than White women. (Hess 2017) Transgender individuals are 3 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV than the national average. Transgender women have a disproportionate risk with an estimated 14% of transgender women living with HIV in 2019. The racial/ethnic disparity is seen within transgender individuals as well with 44% of Black transgender women living with HIV. (Becasen 2019) (See Figure 2.)

| Figure 1: New HIV Diagnoses by Transmission Category, 2017 |

|

| Source: CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017; vol. 29. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2018. |

PrEP Use: Assessing Risk

The CDC has provided clinical guidance for PrEP use since approval in 2012, recommending the daily use of combination FTC/TDF for high-risk MSM, heterosexually active men and women, and intravenous drug users. In order to identify individuals who may benefit from PrEP or other harm reduction techniques, clinicians should routinely obtain detailed sexual history and substance use history from all adult and adolescent patients. A recommended behavior assessment from the CDC includes brief questions designed to flag people who may have sexual practices associated with HIV acquisition risk (e.g., anal receptive sex). At-risk MSM indicated for PrEP include men with any male sex partner within 6 months with anal sex without condoms and/or a bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI). Heterosexually active men and women at risk for HIV acquisition and indicated for PrEP include individuals with an opposite sex partner within the past 6 months who are not in a monogamous partnership with a recently-tested, HIV-negative partner, and at least one of the following: infrequent condom use, sex with an HIV-positive partner, and/or bacterial STI. PrEP is also recommended for persons who inject drugs and report sharing of injection or drug preparation equipment within the past 6 months. (CDC PrEP Guidelines 2017)

Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment for MSM

In the past 6 months:

- Have you had sex with men, women, or both?

- (if men or both) How many men have you had sex with?

- How many times did you have receptive anal sex (you were the bottom) with a man who was not wearing a condom?

- How many of your male sex partners were HIV-positive?

- (if any positive) With these HIV-positive male partners, how many times did you have insertive anal sex (you were the top) without you wearing a condom?

- Have you used cocaine or methamphetamines? (crystal, speed)

Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment for Heterosexual Men and Women

In the past 6 months:

- Have you had sex with men, women, or both?

- (if opposite sex or both sex) How many men/women have you had sex with?

- How many times did you have vaginal or anal sex when neither you nor your partner wore a condom?

- How many of your sex partners were HIV-positive?

- (if any positive) With these HIV-positive partners, how many times did you have vaginal or anal sex without a condom?

PrEP Efficacy

When used effectively with consistent adherence, PrEP with emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate reduces the risk of HIV acquisition over 90%. As shown below (see Table 1), adherence to FTC/TDF is highly correlated with its efficacy. Subgroup analyses of the iPrEx study and Partners PrEP study show that in individuals with detectable drug levels, risk reduction was 92% and 90% respectively. (Grant 2010; Murnane 2012) An open-label extension of study iPrEx showed no HIV infections in persons with drug levels associated with having taken four or more doses per week. PROUD, an open-label and randomized study, also showed high efficacy rates of FTC/TDF with 86% HIV risk reduction. (McCormack 2016) Preliminary data on PrEP efficacy in heterosexual women was limited due to low adherence rates in studies. Results from Partners PrEP and TDF2, however show promising efficacy results in women. TDF as a sole agent has been shown to be effective HIV prevention in persons who inject drugs with 73.5% risk reduction seen in the Bangkok tenofovir study when the drug was taken consistently and in combination with harm reduction strategies. (Choopanya 2013) Efficacy seen in this trial supports the CDC recommendation for use of daily oral PrEP with TDF/FTC or TDF alone as a prevention option for persons who inject drugs.

Newly approved FTC/TAF has been evaluated in one randomized phase III trial known as DISCOVER in cis-gender MSM and transgender women at high risk of HIV infection. FTC/TAF demonstrated noninferiority to FTC/TDF with rates of HIV incidence after 48 weeks of 0.16/100 person years compared to 0.34/100 person years, respectively. (Hare 2019) Sub-analysis of this study showed that FTC/TAF reached protective intracellular drug concentrations quicker than FTC/TDF and these levels persisted longer than FTC/TDF, which may explain the numerically lower number of HIV diagnoses with a TAF based regimen. (Spinner 2019)

There have been a limited number of case reports of PrEP failure, primarily associated with acquiring a drug-resistant HIV strain. (Grant 2014)

| Table 1: FTC/TDF Adherence and Efficacy Rates in Phase II & III Studies |

| Study |

Population |

Adherence* |

Efficacy |

| VOICE (n=1003) |

Heterosexual women |

29% |

~0%** |

| FEM-PrEP (n=1062) |

Heterosexual women |

24% |

6% |

| iPrEx (n=1251) |

Men who have sex with men and transgender women |

51% |

44% |

| TDF2 (n=611) |

Heterosexual men and women |

80% |

62% |

| Partners PrEP (n=1583) |

Heterosexual men and women with HIV positive partners |

82% |

75% |

*by drug level

**stopped early due to futility |

Safety

FTC/TDF used for PrEP is generally well tolerated. In HIV uninfected adults, the most common adverse reactions include headache (7%), abdominal pain (4%), and weight loss (3%). When used in the treatment of HIV positive individuals, TDF has associated risks of renal toxicity and decreases in bone mineral density. (FTC/TDF PI) However, a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled PrEP studies found no significant difference in grade 3 or 4 adverse events when compared to placebo. (Fonner 2016) In a substudy of iPrEx, men who had DEXA scans while receiving FTC/TDF PrEP had a small decrease in spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) compared to placebo, but no difference was seen in fracture rates and BMD recovered after PrEP discontinuation. (Mulligan 2015). In the DISCOVER trial, FTC/TAF and FTC/TDF had similar rates of adverse events in both arms, though FTC/TAF had more favorable safety outcomes with an improved bone mineral density and renal profile compared to FTC/TDF. (See Table 2) For characteristics of FTC/TDF and FTC/TAF, please see Table 3.

| Table 2: DISCOVER Bone and Renal Safety at 48 Weeks |

| Outcome |

FTC/TAF |

FTC/TDF |

P-value |

| Bone Mineral Density (BMD) |

| Spine BMD Mean Change (%) |

+0.50 |

-1.12 |

<0.001 |

| Hip BMD Mean Change (%) |

+0.18 |

-0.99 |

<.001 |

| Renal |

| Median change from baseline GFR (ml/min) |

+1.8 |

-2.3 |

<0.001 |

| Table 3: PrEP/PEP Antiretroviral Drug Characteristics |

| Drug |

Class |

Usual Dosing* |

Renal adjustments |

Drug Interactions |

Side effects |

Clinical Pearls |

| Emtricitabine/ Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) |

NRTI |

200-300 mg daily |

Not recommended in CrCl

<60 ml/min for PrEP and CrCl

<50 ml/min for PEP |

Minimal |

· Headache

· Abdominal pain

· Weight loss

· Renal impairment

· Decrease in bone

mineral density |

Must screen for baseline HBV and HIV

Active against hepatitis B infection |

| Emtricitabine/Tenofovir alafenamide (FTC/TAF) |

NRTI |

200-25 mg daily |

Not recommended in CrCl

<30 ml/min |

Minimal |

· Diarrhea

· Nausea

· Headache

· Fatigue

· Abdominal pain |

Must screen for baseline HBV and HIV

Active against hepatitis B infection

Not recommended for individuals at risk from receptive vaginal sex |

| Raltegravir |

Integrase Inhibitor |

400mg twice daily |

None (DHHS 2019) |

RAL should be administered

2 hours prior or 6 hours after antacids and polyvalent cations. (Calcagno 2015; Kiser 2010)

Strong inducers of UGT1A1 (phenytoin, phenobarbital, etc) should not be used along with RAL. (NYS AI 2019) |

· Insomnia

· Headache

· Dizziness

· Nausea

· Fatigue

· Elevations in CK

· Myopathy

· Depression |

Black box warning for severe skin and hypersensitivity reactions; RAL should be discontinued if any of these occur |

| Dolutegravir |

Integrase Inhibitor |

50mg daily |

None, however DTG inhibits tubular secretion of creatinine which may increase serum creatinine levels without affecting glomerular filtration rate (DHHS 2019) |

DTG should be administered

2 hours prior or 6 hours after iron salts or divalent or trivalent cations (aluminum, magnesium, calcium). (Song 2015; Cottrell 2013)

DTG should not be coadministered with dofetilide or valproic acid. (NYS AI 2019; Max 2014; Feng 2016)

Max daily dose of metformin is 1000mg when used in combination with DTG. (NYS AI 2019; Song 2016; Gervasoni 2017) |

· Insomnia

· Headache

· Dizziness

· Nausea

· Fatigue

· Depression

· Weight gain |

Hypersensitivity reactions reported with rash, constitutional findings and organ dysfunction; DTG should be discontinued if any of these occur |

NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

*Usual dosing for PEP and PrEP |

FDA labeling includes black box warnings for severe acute exacerbations of hepatitis B when FTC/TDF or FTC/TAF is discontinued in hepatitis B infected individuals and for the risk of drug resistant HIV when given to patients with undetected acute HIV infections. FTC/TDF and FTC/TAF are effective treatments for hepatitis B and stopping treatment in a patient with active hepatitis B infection could lead to a flare. Therefore it is recommended to screen individuals for hepatitis B at baseline, immunize if susceptible, and monitor closely after discontinuation if surface antigen positive. (FTC/TDF PI; FTC/TAF PI) See Table 4 for recommended lab monitoring at baseline and follow-up.

PrEP is not an effective HIV treatment regimen and should only be given to patients who are confirmed to be HIV negative immediately prior to use (within 1 week) and who are screened for HIV every 90 days while on treatment. (FTC/TDF PI; FTC/TAF PI) In addition, patients should be screened for signs and symptoms of acute HIV infection as they may falsely screen as HIV negative during the window period. In phase II and III PrEP studies, TDF- or FTC-resistant HIV was seldom detected and nearly all cases were from individuals who were inappropriately screened and infected at baseline prior to PrEP initiation. (CDC PrEP Guidelines 2017) Real world surveillance data from New York City show that individuals recently diagnosed with HIV were more likely to have a virus strain resistant to emtricitabine if they had ever been on PrEP (29% vs 2%). There were no tenofovir-resistant mutations identified among PrEP users. It is difficult to discern from surveillance data whether resistance was acquired or transmitted, but it highlights the importance of initial and continued HIV screening while on PrEP. (Misra 2019)

Clinical trials and real world reports have shown high rates of STIs among individuals using PrEP. There has been a concern that PrEP use could lead to risk compensation and changes in sexual behavior like using condoms less frequently or increase in sexual partners. (Gandhi M 2019) PrEP use should be recommended in addition to safer sex practices including condom use and frequent STI screening. Many STIs are asymptomatic, and the high rates found in PrEP users may be associated with increased testing. This was evident in an analysis of an Australian based PrEP campaign which showed that although STI incidence increased 41% from preenrollment, when individuals were adjusted for testing frequency, the increase was 14%. (Traeger 2019)

| Table 4: Recommended Lab Monitoring |

| Lab Test |

Initial Screening |

At Least Every 3 Months |

At Least Every 6 Months |

As Indicated |

| HIV immunoassay |

X |

X |

|

|

| HIV viral load |

|

|

|

X - if signs of acute HIV OR have a negative antibody test but report condomless anal or vaginal sex in the previous 4 weeks (NYSDOH) |

| Hepatitis B serologies |

X |

|

|

|

| Scr/eGFR* |

X |

|

X |

|

| Bacterial STIs |

X |

|

X |

|

| Pregnancy test |

X |

X - for receptive

vaginal intercourse |

|

|

| *FTC/TDF should only be considered in individuals with an eCrCl > 60 ml/min |

PrEP Uptake

Although the United States has already surpassed the 2020 target of PrEP prescriptions with over 64,000 persons prescribed PrEP in 2016, this is still far below the estimated 1.1 million Americans who are at risk of acquiring HIV. (CDC 2019; Huang 2018) Since 2012 there have been local, statewide, and national efforts to increase community awareness of PrEP, but there continues to be major barriers to PrEP uptake and large disparities based on gender and race. In 2017, 90% of at-risk MSM were aware of PrEP, yet only 34% of men reported using PrEP. This rate was substantially lower in Black and Hispanic men, 26% and 29% respectively, compared to white men at 42%. (Finlayson 2019) Although 19% of new HIV diagnoses in 2017 were women, they were less likely to be prescribed PrEP with only 4% of active PrEP prescriptions being filled for women. (CDC 2018; Siegler 2018) Sexually-active Black and Latina women were surveyed in New York City, and less than 25% of them reported being aware of PrEP. (Gandhi A 2016) There continues to be significant patient and provider barriers regarding access to PrEP, including stigma, lack of patient and provider education, limited LGBT inclusive medical care, geographic isolation, cost, and more.

A Pharmacist’s Role in PrEP

As one of the more accessible providers of health care services, pharmacists are well positioned to help overcome barriers to PrEP uptake. In 2016, over one fifth of MSM lived in a “PrEP desert” with the nearest PrEP provider being over a 30 minute drive away, whereas over 90% of the US population lives within 2 miles of a pharmacy. (Weiss 2018; Qato 2017) Pharmacists interact with patients at many points of care throughout the healthcare system including at community pharmacies, during inpatient hospitalizations, and in primary and specialty care clinics, thus pharmacists in a variety of settings can play a major role in PrEP uptake and retention.

Many pharmacists are routinely involved in sexual health counseling in the community and are well positioned to screen patients and educate at-risk individuals about PrEP. PrEP education and risk reduction counseling may be appropriate for patients obtaining prescriptions for sexually-related conditions including STIs, erectile dysfunction, contraception, HIV post exposure prophylaxis, and over the counter items like condoms, lubricants, and at home HIV tests. (Farmer 2019) Patients seeking services surrounding injection drug use like naloxone, syringes, and medication assisted treatments may also be counseled by pharmacists. These situations are opportunities to discuss HIV vulnerabilities, need for PEP, PrEP availability, and harm reduction strategies.

In order to maintain accessibility it is essential that pharmacists provide nonjudgmental, inclusive information for patients and avoid assumptions, particularly surrounding gender identities, sexual orientation, and sexual practices. It is important to be especially cognizant of populations in which PrEP is underutilized like transgender individuals, men who have sex with men, women, and particularly Blacks, and Hispanics. Pharmacists should access LGBT resources to become familiar with culturally-appropriate terminology to encourage effective communication. Open dialogue surrounding sexual health and drug use may reduce the distrust of the healthcare system and stigma associated with PrEP use.

LGBT Field Guide: https://www.jointcommission.org/lgbt/

National LGBT Health Education Center: https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/

In a 2016 survey of men who have sex with men using sexual networking sites, over a quarter of men surveyed reported concern of potential adverse events being a reason for not using PrEP. (Mayer 2017) As medication experts, pharmacists may not only educate patients about PrEP availability and efficacy, but also address common misconceptions surrounding treatment including potential side effects and medication interactions.

For individuals who are prescribed PrEP, pharmacists can play a key role in medication adherence counseling and monitoring. As shown in the major clinical trials, adherence is the major driver of PrEP success. Prior to PrEP initiation individuals should be provided information about the importance of adherence and time to protection – 7 days in rectal tissue, 20 days in blood and vaginal tissue for FTC/TDF. Adherence should be assessed at every visit. Also at each visit additional resources that may help maintain or improve adherence like pill boxes, electronic reminders, or blister packed medications should be provided. (Bruno 2012) Adherence can be measured through self-report, refill history, and/or therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). TDM can be considered periodically, though there is not yet an established concentration associated with PrEP efficacy. The only commercially available PrEP TDM is a urine test, though blood and hair analysis is being evaluated in research studies. Currently available TDM is not a valid estimate of consistent adherence as it only reflects recent dosing.

Pharmacists practicing in many settings can act as a key member of the PrEP care team to help overcome barriers to care. Over 30% of US MSM reported not knowing where to access PrEP as a reason for not utilizing PrEP. (Mayer 2017) As highly-accessible providers, pharmacists are in a critical position to refer patients to clinics that provide PrEP and should be prepared with resources to distribute to patients. There are state-specific and national databases that can help identify PrEP providers based on location. Relationships between local PrEP providers and pharmacists should be encouraged for effective referral and retention practices.

Resources for Finding PrEP Providers

https://preplocator.org/

https://pleaseprepme.org/

https://npin.cdc.gov/preplocator

In the past few years, pharmacist-led PrEP services have been implemented in both community pharmacies and ambulatory care settings through collaborative practice agreements (CPAs). Community pharmacies in states including Missouri, Washington, and Colorado have developed clinics for PrEP initiation, continuation, dispensing, and monitoring. In order to provide comprehensive testing and care, some of these practices trained pharmacists as phlebotomists to allow for onsite lab testing. The pharmacy as a setting of PrEP delivery may be preferred by patients as being less stigmatizing than an infectious disease or sexual health clinic, or as having improved convenience, proximity and extended hours. (Farmer 2019) At One-Step PrEP™ clinic in the Kelley-Ross Pharmacy in Seattle, Washington, over 75% of their patients reported not having a primary care provider at initiation, which suggests that these community pharmacy-based PrEP services may expand PrEP beyond traditional health care models. (Tung 2017)

Ambulatory clinic-based, pharmacist-led PrEP clinics in New Mexico, New York, and Missouri with CPAs allow clinical pharmacists to work independently to provide comprehensive sexual health visits with risk assessment, STI screening, lab monitoring, and PrEP prescribing when appropriate. In October 2019, California passed a law authorizing pharmacists to dispense and furnish medications for PrEP after completing a board approved training program. Pharmacists will be able to dispense up to 60 day supply of FTC/TDF or FTC/TAF after confirming a negative HIV test within 7 days, reviewing patients other medications, checking for symptoms of acute HIV, and providing in depth counseling. Pharmacists are only able to furnish up to 60 day supply every 2 years, so patients will need to be referred to local PrEP providers in the community for continuation. The California state board plans to have these regulations implemented by July 2020 in order to expand access to PrEP in the community. (California Legislative Information, 2019)

Pharmacists as providers of PrEP has a number of advantages including experience with medication adherence counseling, ability to monitor and recognize potential side effects or drug-drug interactions, and expertise in navigating medication coverage and payment options. (Farmer 2019)

The current out of pocket cost for a month’s supply of FTC/TDF can be over $2,000 without insurance and can often have high copays for individuals on commercial insurance plans or Medicare. Pharmacists are well equipped to help patients navigate insurance coverage, obtain prior authorizations, and explore alternative funding for those who are uninsured or underinsured. Many states have PrEP drug assistance programs and there are manufacturer patient assistance programs and copay cards that can bring out of pocket medication costs to zero.

Pharmacists are key members of the PrEP care team and should be encouraged to be involved in screening, education, monitoring, and other services in order to continue to improve PrEP access and adherence, increase uptake, and reduce transmission of HIV. As more medications are approved for HIV prevention (See next section), pharmacists may have future opportunities for drug delivery as well.

Emerging Strategies for Prevention*

* Note: this section contains off-label discussion

A number of different agents in the pipeline for HIV prevention would allow for alternative dosing strategies that may improve PrEP adherence or tolerability. FDA approved FTC/TDF has been evaluated as an off-label “on-demand” dosing schedule of 2 tablets of FTC/TDF taken 2-24 hours prior to sexual intercourse and 1 tablet taken at 24 hours and 48 hours after intercourse. In a randomized study compared to placebo, on-demand peri-coital dosing had a relative reduction in HIV incidence of 86% in a MSM population. In this study, individuals reported taking a median of 15 pills per month. (Molina 2015) This dosing strategy may be an option to limit toxicities from daily drug exposure, particularly in individuals with only episodic risk. International guidelines including the World Health Organization and the European AIDS Clinical Society do consider it an optional recommendation for MSM with high-risk sexual behavior, though CDC guidelines do not currently recommend this regimen due to concerns surrounding whether this dosing schedule would be efficacious in a population with lower frequency of sex and therefore less cumulative drug exposure. (WHO Guidelines; EACS Guidelines)

Another focus of PrEP development is the investigation of long-acting formulations of ARVs which could improve adherence and convenience for a larger population.

A long-acting (LA) injectable integrase inhibitor cabotegravir was shown to be well tolerated and had high patient satisfaction in phase II studies. A dose of 600 mg of cabotegravir injected every 8 weeks met pharmacokinetic targets in both men and women and is currently being evaluated in phase III studies. (Landovitz 2018) LA-cabotegravir has a long lasting pharmacokinetic tail with its half life around 42-66 weeks, depending on sex. This long half life of subinhibitory concentrations of cabotegravir could lead to drug resistant virus if an individual is infected in the post drug period. If cabotegravir is approved for prevention, this long PK tail would likely require an oral preventative agent after injectable discontinuation. (Radzio-Basu 2019)

An intravaginal ring embedded with the antiretrotriviral dapivirine has been evaluated in phase III clinical trials for prevention and was found to reduce the risk of HIV infection in African women by 30%. (Baeten 2017) The ring placed monthly was found to be well tolerated and is also being evaluated at higher doses to provide protection for 90 days at a time.

A first-in-class nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), islatravir, has been shown to protect against simian HIV in animal studies with weekly dosing and its long half life may allow for long-acting PrEP formulations. A removable subdermal islatravir-eluting implant prototype is currently being evaluated as a once-yearly PrEP option in phase 1 and 2 studies. (Matthews 2019) Novel formulations like the intravaginal ring and drug eluting implant may allow for co-formulation with contraceptives for prevention in cis-gendered women.

CASE 1

Daisy is an African-American, 28-year-old, transgender female who presents to the pharmacy for refills on her estradiol patches and with a new script for azithromycin 1g for treatment of chlamydia. While counseling her on her new medications, she mentions this is the 2nd STI she has been diagnosed with in the past year. You perform a thorough social history and learn she engages in receptive anal and oral sex and occasionally uses methamphetamine when having sex. She has had around 10 partners in the past 6 months and does not always use condoms. You decide to ask her if she’s ever heard of PrEP.

Pause and Reflect:

Consider the following questions about the above case, then listen to commentary from our faculty educators.

- What potential barriers to PrEP use can you identify?

- What education should be provided to Daisy?

- If prescribed PrEP, what agent should be used and what baseline tests should be done?

|

PEP: A Tool for HIV Prevention

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is a method of HIV prevention in which an individual takes antiretroviral therapy after a potential exposure to HIV in order to block HIV from establishing an infection in the body. This section will focus on non-occupational exposures including sexual contact (however, not sexual assault) and needle-sharing. Occupational exposures (i.e. needle stick) should be promptly treated to prevent HIV as well.

PEP Efficacy

Randomized, placebo-controlled trials to demonstrate the efficacy of PEP have not been conducted and are not ethical or feasible to design. Published guidelines and best practices have been developed from data gathered that indicate it is plausible to block HIV infection from establishing itself if antiretroviral therapy is initiated soon after the exposure. Most notable are studies looking at the prevention in animal studies following exposure (Otten 2000; Smith 2000; Van Rompay 2000) as well as mother-to-child transmission. (Connor 1994) Data from a retrospective study assessing zidovudine to prevent HIV after occupational exposures show an 81% risk reduction. (Cardo 1997) Non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) was deemed to be cost effective in the scenario of high-risk exposures such as condomless, receptive anal sex with a partner who is HIV-positive or of unknown status. (Pinkerton 2004; Herida 2006)

Data from animal models indicate that antiretrovirals are most effective at preventing HIV from establishing an infection if taken within 24 to 36 hours post-exposure. Every effort should be made to initiate PEP as soon as possible from the time of the exposure, ideally within 2 hours. It is unlikely that PEP will be effective after 72 hours from exposure. (CDC 2016) Exposures should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis taking into consideration the time from exposure, exposure risk and the HIV status of the source patient. (NYS AI 2019)

Certain factors increase the risk of HIV transmission after exposure. The source patient’s HIV-status and viral load is particularly significant in the potential for HIV transmission. The risk of transmission increases with high viral loads and it has been noted that transmission is 8 to almost 12 times more likely to occur during acute HIV infection. (Wawer 2005; Pilcher 2004) During acute HIV infection, it is likely the source patient is unaware of their HIV status. Other conditions that may increase the risk for HIV transmission include lack of barrier protection (i.e. condoms), presence of genital ulcer disease or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), trauma at the site of exposure, and if the oral mucosa is not intact (i.e. oral lesions, gingivitis, wounds). (NYS AI 2019)

PEP Prescribing Pearls

Prior to initiating PEP, the provider and patient should discuss the risk of the exposure and the potential benefit of PEP as reviewed in Table 5. Timing between the exposure and the start of medications is vital in maximizing treatment efficacy as PEP initiated 72 hours after the exposure is unlikely to be effective. (Otten 2000) For individuals taking PrEP daily, PEP is not indicated despite high risk exposure. However, if adherence was inconsistent or the individual was not taking PrEP the week before the exposure, PEP may be considered. (CDC 2016)

| Table 5: HIV Transmission Risk by Type of Exposure |

| Type of Exposure |

Risk per 10,000 Exposures |

| Blood transfusion |

9,000 |

| Needle-sharing during injection drug use |

67 |

| Receptive anal intercourse |

50 |

| Percutaneous |

30 |

| Receptive penile-vaginal intercourse |

10 |

| Insertive anal intercourse |

6.5 |

| Insertive penile-vaginal intercourse |

5 |

| Receptive oral intercourse |

Low |

| Insertive oral intercourse |

Low |

| Biting |

Negligible |

| Spitting |

Negligible |

| Throwing body fluids |

Negligible |

| Sharing sex toys |

Negligible |

| Source: CDC 2015 |

Adherence to the PEP regimen for the duration of treatment is paramount to HIV prevention. Therefore it is important to have a plan in place for the individual to be able to obtain the full 28-day course of PEP—especially in the scenario where a starter-pack is given. Starter-packs are often dispensed from emergency departments to allow quick access to PEP. The remaining course of therapy is typically dispensed out of a community pharmacy. It has been shown that individuals who received starter packs of PEP compared to those who received the full course of therapy were less adherent, 29% vs. 71% respectively. (Kim 2009) Not all community pharmacies maintain a stock of antiretroviral medications which may cause a delay in continuation of therapy. There are also challenges from a community pharmacy perspective when they dispense a high-cost medication, such as an antiretroviral, at a quantity less than the full bottle. These situations can be barriers to access or adherence.

A three drug regimen is recommended for PEP based on extrapolated data that indicates the effectiveness of combination therapy on viral suppression. In the event the exposure was of a resistant HIV virus, three drugs are more likely to combat resistance than a regimen containing fewer drugs. (Kuhar 2013) The preferred PEP regimen is tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC) 300mg/200mg once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50mg once daily. (CDC 2016) Both regimens are well tolerated and have been shown to be effective at treating HIV. (NYS AI 2019)The two preferred options for PEP only differ by the integrase inhibitor within the regimen. Therapy should be individualized. RAL is preferred in individuals of childbearing potential or those in their first trimester of pregnancy however it is taken twice daily. The regimen containing DTG is taken once daily which may enhance adherence to PEP. Both regimens include TDF/FTC. TDF is renally eliminated. Individuals who have renal impairment (CrCl < 50 mL/min) may require a dose adjustment. (NYS AI 2019; TDF PI 2019) Studies looking at integrase-based PEP regimens show good tolerability as well as adherence. (Annandale 2012; Mayer 2012) Although both regimens are considered well tolerated, side effects associated with each individual agent are discussed previously in Table 2.

Preliminary data from a 2018 observational study have shown that DTG was associated with a higher rate of neural tube defects when administered at the same time as conception and in early pregnancy. (Zash 2018) Additional data released in 2019 showed less neural tube defects in babies born to individuals on DTG than originally indicated. (Zash 2019) In the US, it is recommended to avoid DTG use in people of child-bearing potential through the first trimester of pregnancy. DTG should be replaced with another appropriate antiretroviral if the individual would like to try to get pregnant or if a pregnancy is confirmed. (DTG PI 2018)

Alternative PEP regimens can be considered based on the information available on the source patient. If the source patient is infected with HIV, their viral load, past or current antiretroviral regimens and resistance profile can be used by the provider to tailor the PEP regimen to maximize effectiveness. However, the first dose of PEP should not be delayed if this information is not readily available. If necessary, the PEP regimen can be altered when the source patient’s information becomes available. PEP regimens can be switched if the individual is having tolerability issues as well. (NYS AI 2019)

Baseline Evaluation

In order to rule-out baseline HIV infection, an HIV screen should be done on the exposed individual when initiating PEP. Preferably a rapid, fourth-generation HIV antigen/antibody screen should be completed on initial presentation. If the test is reactive, confirmatory tests should be completed and guidelines for the treatment of HIV should be followed. If the exposed individual is in the window period of the HIV screen and the screen is negative, the provider may consider ordering an HIV RNA to rule out acute HIV infection. (NYS AI 2019) The HIV RNA is generally detectable 7 to 14 days post exposure whereas the HIV antigen/antibody screen takes 4 to 8 weeks to detect HIV biomarkers. (Alere 2013) There should be no delay in PEP initiation if an HIV RNA is ordered. If HIV RNA returns detectable, guidelines for treatment of acute HIV infection should be followed. If HIV RNA returns negative, PEP should be continued. Negative baseline HIV screening of the exposed individual indicates the person was not previously infected with HIV. It cannot determine if the individual has been infected with HIV from the exposure of which they are presenting. (NYS AI 2019)

Screening for other STIs should be completed upon presentation as well. This includes gonorrhea and chlamydia tested at all sites of potential exposure as well as syphilis. Empiric treatment should be considered in the presence of symptoms or known exposure. Education should be provided to the individual about signs and symptoms of STIs and what to do in the event they occur. (NYS AI 2019)

Since there are similar risk factors, assessment for exposure to both hepatitis B and C should be completed by the provider. If potential exposure occurred, post-exposure recommendations for hepatitis B and C should be included in the care plan. To obtain baseline kidney and liver function, a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) is recommended. (NYS AI 2019; CDC 2016)

A pregnancy test should be completed upon initial presentation. If the person is of child-bearing potential or in their 1st trimester of pregnancy, PEP should be offered using TDF/FTC plus RAL. If the pregnancy test is negative, emergency contraception should be offered. If the person who was exposed is breastfeeding, consideration should be made to discontinue breastfeeding until it is confirmed the source patient is not infected with HIV. If this cannot be done, the individual should be advised to withhold breastfeeding for 3 months until seroconversion can be ruled out. (Parkin 2000; NYS AI 2019)

Duration of Treatment

PEP should be administered for 28 days after a potential exposure from a source patient who is infected with HIV or who is unavailable or unwilling to undergo HIV screening. If the source patient is willing to complete HIV screening, PEP should be initiated until results are available. If HIV screen returns non-reactive and the source patient has not had any potential exposures to HIV in the last 6 weeks, PEP can be discontinued. Plasma HIV RNA, or viral load, should be considered for the source patient if their HIV screen was non-reactive but there was potentially an exposure in the last 6 weeks to rule out acute infection. If the HIV RNA results are detectable, PEP should be continued for 28 days. If the HIV RNA is negative, PEP can be discontinued. (NYS AI 2019)

Monitoring

Individuals should have follow-up within 3 days and weekly after starting PEP to assess adherence and side effects. Adherence tools should be offered including pill boxes, phone call or text reminders, alarms, mobile phone adherence applications or enrolling in a treatment adherence program. Side effects are typically minimal, managed with over-the-counter agents and resolve after 1-2 weeks on therapy. If side effects are resulting in a barrier to the patient taking their PEP regimen, follow-up with the prescribing provider is recommended to consider alternative PEP regimen. (NYS AI 2019)

Safer sex and harm reduction counseling should be provided to the exposed patient. Until the completion of PEP treatment and HIV screening through 12 weeks, it is recommended the individual use barrier protection during sexual encounters, avoid pregnancy or breastfeeding, avoid needle-sharing and to refrain from donating blood. If ongoing risk is present, the person should be started on PrEP for HIV after completion of PEP. (NYS AI 2019)

HIV testing should be completed again at 4 weeks and 12 weeks post-exposure. HIV antigen/antibody serologic testing is recommended. If results are reactive, confirmatory testing should be completed to establish an HIV diagnosis. If at any time the exposed patient presents with signs or symptoms (i.e., fever, flu-like symptoms, rash) of acute HIV infection, HIV screening should be completed along with an HIV RNA to rule out acute HIV infection. (NYS AI 2019)

Screening for STIs should be considered at the 4 week follow-up if presumptive treatment was not provided upon initial presentation or the patient reports signs or symptoms of STIs. Repeat CMP is recommended at this time. (CDC 2016)

PEP to PrEP

A comprehensive sexual history and drug use assessment should be completed with all individuals receiving PEP. For those with ongoing vulnerabilities, PrEP is an important tool to empower patients to remain HIV negative. A seamless transition from PEP to PrEP is recommended for those with continuing risk factors (See PrEP as a Tool for Preventing HIV Infection section above). PrEP should be started as soon as possible after the 28 day course of PEP has been completed. HIV screening should be done at this time, preferably with fourth generation HIV antigen/antibody testing, to rule out seroconversion from the exposure that prompted PEP initiation. An HIV RNA may be ordered as well if acute HIV is in question or adherence has been suboptimal to PEP. If HIV screen is reactive, treatment guidelines for HIV should be followed opposed to starting PrEP. (CDC 2016; UCSF 2016)

Individuals may defer or decline PrEP after completion of PEP. Utilizing the sexual history and drug use assessment gathered at baseline and updated at the 4 week follow-up, the provider and individual should develop an HIV prevention care plan that includes HIV testing. Risk factors associated with HIV are often fluid so it is important to review the resources the person can utilize if they are in need of PEP or PrEP in the future. (NYS AI 2019; UCSF 2016)

A Pharmacist’s Role in PEP

Pharmacists are key members of the interprofessional team that promotes HIV prevention, regardless of the setting they practice in.

Clinical pharmacists work directly with the patient care team including prescribing providers, nurses, case managers and the patients themselves to optimize medication regimens to promote better health outcomes and quality of life. One strategy to optimize the use of a clinical pharmacist and their expertise in medication therapy is to develop a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) between a provider and pharmacist. Collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM) utilizes a CPA to allow pharmacists to assume professional responsibility for performing patient assessments, counseling, ordering labs, prescribing medications and making referrals for a patient. State laws and regulations around CDTM vary from state to state. (CDC 2013)

For clinical pharmacists practicing under CDTM, HIV prevention is an area of potential. As the experts in medication therapy, management of side effects, adherence optimization and insurance navigation, pharmacists are key members of the care team to provide PEP (as well as PrEP) services to patients.

A crucial responsibility of the community or emergency medicine pharmacist is ensuring the person’s understanding of the medication regimen being dispensed to them and developing a plan to promote adherence. Ways to promote adherence to PEP include pillboxes or pill key chains, promoting technological tools such as alarms or mobile applications and potential offerings of the community pharmacy itself including automatic refills, text reminders that prescription is ready for pick up or due for a refill as well as delivery. Encouraging the person to notify the pharmacist of any new medication they are taking, including non-prescription drugs, supplements or vitamins, can reduce the chance for drug interactions that may lower the effectiveness of PEP. Pharmacists working in hospital settings also can play a key role in developing order sets in the electronic medical record to ensure PEP candidates are offered the treatment and that the right labs and medications are dispensed to the patient. They can also assist with protocol development and education to other staff members throughout the hospital.

The community pharmacist should also be utilized as a resource in side effect management as they can assist the individual in choosing an appropriate over-the-counter agent to control side effects, reducing the chance of missed doses. The pharmacist may also identify a reason that communication with the prescribing provider is warranted and can facilitate that.

In March 2017, New York became the first state to allow patients to access PEP from a community pharmacy setting prior to seeing a prescribing provider. The rationale for implementing this new regulation was that community pharmacists are trusted and accessible members of the care team and can facilitate early initiation of PEP. Utilizing a non-patient specific standing order (similar to those used for immunizations), pharmacists are able to assess the need for PEP and dispense a 7-day supply to those who are in need. The pharmacy team then links the exposed patient to a provider or clinic that can provide a comprehensive baseline evaluation, a prescription for the remaining 28-day regimen and ongoing care. To learn more, visit https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/pep/pharmacies.htm. (NYSDOH 2017) In October 2019, the same California law authorizing pharmacists to provide PrEP also authorized them to provide PEP. Pharmacists who have completed a training program approved by the board can dispense the complete course of PEP to a patient who presents to the pharmacy within 72 hours of a potential exposure. HIV screening is recommended however PEP can still be dispensed if the patient refuses. Pharmacists then notify primary care providers or provide the patient with a list of providers for PEP follow-up care. (California Legislative Information, 2019)

Overcoming the Barrier of Cost

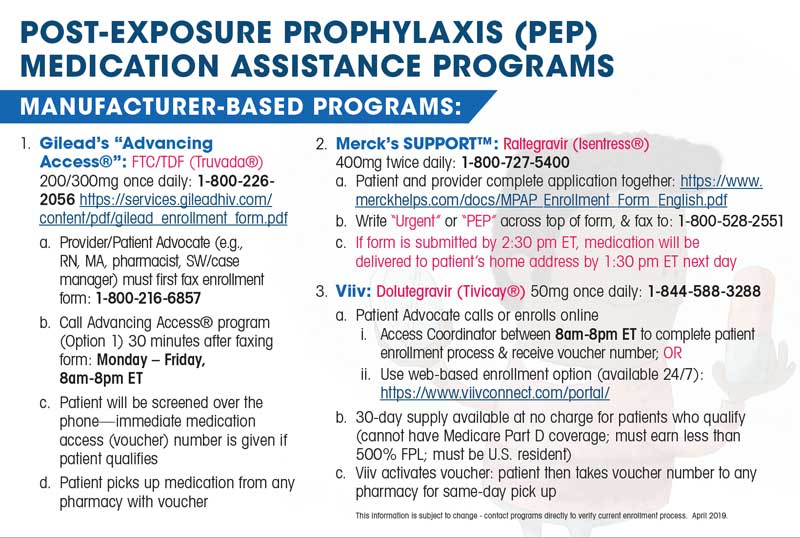

Cost is often a barrier to individuals starting or completing a full course of PEP. However, there are several manufacturer and state specific assistance programs that can assist the patient in obtaining medication at little or no cost. To reduce the out–of-pocket cost to the patient with commercial insurance and copays or deductibles on prescription medications, often a manufacturer copay coupon can be used. For PEP, manufacturers have also developed programs to cover the cost of PEP medication in entirety. Steps to ensure quick access to full coverage of the medications can be seen in Figure 3.

| Figure 3 |

|

| Source: AETC 2018. All additional materials can be downloaded and printed as needed. |

In addition to manufacturer-based programs, there is a federal foundation—Patient Advocate Foundation—that offsets the costs of copays for patients who qualify. To access this program, providers must register at https://www.copays.org/providers. The application process takes approximately 10 minutes and eligibility is determined by completion of a Patient Enrollment Application. This can be completed by the provider on behalf of the patient. Patient information required to apply includes reported income, diagnosis and insurance coverage information. Patients may be subject to review of income documentation within 30 days of approval date. (AETC 2018)

CASE 2

Jay is a 19-year-old, African American, gay male who works as a waiter in New York City. He presents to urgent care reporting a condom break the night before with an anonymous partner. He was engaging in receptive anal sex. There were no significant findings on physical exam. PMH: n/a. He is sexually active however he is not in a mutually monogamous relationship; he reports 6 partners in the last 3 months with inconsistent condom use but typically “knows” his partners. He smokes 1/2 ppd x 1 year, and binge drinks only on the weekends; he denies illicit drug use. Additional information: Meds: None. Allergies: NKDA. Vitals: BP 106/72; P 75; T 98.7 F; GFR > 60.

Pause and Reflect:

Consider the following questions about the above case, then listen to commentary from our faculty educators.

- Based on Jay’s presentation, what labs are recommended?

- What type of treatment is needed for Jay?

- What is the most comprehensive recommendation for Jay to remain HIV negative?

|

Summary

In order to end the HIV epidemic, prevention efforts must be utilized in combination with improved HIV screening and treatment. There is a wide array of tools to promote HIV prevention, including behavioral modifications and biomedical interventions. All members of the interprofessional care team, including pharmacists, are responsible for promoting approaches that can provide patients with better health outcomes such as PrEP and PEP.

Detailed sexual and social histories should be evaluated in all adult and adolescent individuals seeking medical care. PrEP should be offered to high risk individuals to prevent HIV transmission. PEP should be discussed and offered to all individuals who present with a potential exposure to HIV. Medications used for PrEP and PEP today are accessible, well tolerated and easy to adhere to. Cost should not be considered a barrier to care as there are many programs to assist with copays and deductibles related to PrEP and PEP medications.

Biomedical interventions for HIV prevention, such as PrEP and PEP, are underutilized. Reasons for this include lack of awareness, access, fear of being stigmatized and perceived barriers around cost, side effects and risk. Pharmacists can play an integral role in overcoming these barriers as medication experts within the care team. To combat these barriers, sexual health and HIV prevention should be part of routine care, and universal education around PrEP and PEP should be provided to all patients regardless of risk. By utilizing this approach, individuals are prepared to make informed decisions that may impact their health for the rest of their lives.

Resources

The Licensed Pharmacist’s Role in Initiating HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis: Overview and Frequently Asked Questions. NYSDOH. December 2017. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/general/pep/docs/pharmacists_role.pdf

Pharmacy Essentials for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. Clinical Care Options. December 2018. Pharmacy PrEP IVP - HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis - Pharmacy-Based Care - HIV - Clinical Care Options

Non-Occupational Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (nPEP) Toolkit. AIDS Education & Training Center Program. January 2018. https://aidsetc.org/npep

AETC National Clinician Consultation Center's (NCCC) Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline).

888-HIV-4911 (888-448-4911) 9:00 AM - 9:00 PM ET, 7 days/week

LGBT Field Guide. https://www.jointcommission.org/lgbt/

National LGBT Health Education Center. https://www.lgbthealtheducation.org/

Resources for Finding PrEP Providers.

https://preplocator.org/

https://pleaseprepme.org/

https://npin.cdc.gov/preplocator

Bibliography

Alere Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo. Yavne, Israel. Orgenics, Ltd. Revised August 2013.

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP Guidelines on Pharmacist Involvement in HIV Care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2016; 73:e72-98.

Annandale D, Richardson C, Fisher M, et al. Raltegravir-based post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP): A safe, well-tolerated alternative regimen. J Int AIDS Soc 2012;15(Suppl 4):18165.

Becasen JS, Denard CL, Mullins MM, Higa D, Sipe TA. Estimating the Prevalence of HIV and Sexual Behaviors Among the US Transgender Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 2006-2017. Am J Public Health. 2019; 109:e1-8.

Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399-410.

Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, et al. Use of a Vaginal Ring Containing Dapivirine for HIV-1 Prevention in Women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2121-32.

Bruno C, Saberi P. Pharmacists as providers of HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:803–806.

Calcagno A, D’Avolio A, Bonora S. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of raltegravir and experience from clinical trials in HIV-positive patients. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2015;11(7):1167-1176.

California Legislative Information. SB-159 HIV: preexposure and postexposure prophylaxis. Available at: https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB159. Accessed October 15, 2019.

Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1485-1490.

Case of the Month: Transitioning from PEP to PrEP. Clinician Consultation Center UCSF. https://nccc.ucsf.edu/2016/02/29/case-of-the-month-transitioning-from-pep-to-prep/. February 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC HIV Prevention Progress Report, 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Collaborative Practice Agreements and Pharmacists’ Patient Care Services: A Resource for Pharmacists. Atlanta, GA: US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America. https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/index.html. Published June 24 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Risk Behaviors. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/estimates/riskbehaviors.html. 2015.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2017; vol. 29. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated Guidelines for Antiretroviral Postexposure Prophylaxis After Sexual, Injection Drug Use, or Other Nonoccupational Exposure to HIV. www.cdc.gov. 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: US Public Health Service: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Published March 2018.

Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083-2090.

Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatrics AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1173-1180.

Cottrell ML, Hadzic T, Kashuba AD. Clinical pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and drug-interaction profile of the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir. Clin Pharmacokinet 2013;52(11):981-994.

Dolutegravir package insert. Research Triangle Park, NC. ViiV Healthcare. Revised September 2018.

Dolutegravir. AIDSInfo U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. March 2019.

EACS European AIDS Clinical Society Guidelines version 9.1, October 2018.

Emtricitabine package insert. Foster City, CA. Gilead Sciences. 2018.

Emtricitabine. AIDSInfo U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. November 2018.

Farmer EK, Koren DE, Cha A, Grossman K, Cates DW. The Pharmacist's Expanding Role in Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2019;33(5):207-13.

Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844-5.

Feng B, Varma MV. Evaluation and quantitative prediction of renal transporter-mediated drug-drug interactions. J Clin Pharmacol 2016;56 Suppl 7:S110-121.

Finlayson T, Cha S, Denson D et al. Changes in HIV PrEP Awareness and Use Among Men who have Sex with Men, 2014 vs 2017. CROI 2019.Abstr 972

Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS. 2016;30(12):1973-83.

FTC/TAF [package insert] Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences Inc; 2017.

FTC/TDF [package insert] Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences Inc; 2018.

Gandhi A, Appel E, Scanlin K, Myers JE, Edelstein Z. PrEP awareness, interest, and use among women of color in New York City, 2016. Paper presented at: 12th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; June 4–6, 2017; Miami, FL.

Gandhi M, Spinelli MA, Mayer KH. Addressing the Sexually Transmitted Infection and HIV Syndemic. JAMA 2019;321(14):1356-58.

Gervasoni C, Minisci D, Clementi E, et al. How relevant is the interaction between dolutegravir and metformin in real life? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75(1):e24-e26.

Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820-829.

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587-2599.

Hare CB, et al. Abstract 104LB. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 4-7, 2019; Seattle.

Herida M, Larsen C, Lot F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis in France. AIDS 2006;20:1753-1761.

Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime Risk of a Diagnosis of HIV Infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238-43.

Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, Hoover KW. HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis, by Race and Ethnicity — United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1147–1150.

Kim JC, Askew I, Muvhango L, et al. Comprehensive care and HIV prophylaxis after sexual assault in rural South Africa: the Refentse Intervention Study. BMJ. 2009;338:b515.

Kiser JJ, Bumpass JB, Meditz AL, et al. Effect of antacids on the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir in human immunodeficiency virus-seronegative volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010;54(12):4999-5003.

Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al. Updated US Public Health Service guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(9):875-892.

Landovitz RJ, Li S, Grinszrwjn B, et al. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002690.

Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, al . Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372(6):509-18.

Matthews R. First-in-Human Trial of MK-8591-Eluting Implants Demonstrates Concentrations Suitable for HIV Prophylaxis for at Least One Year 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2019), July 21-24, 2019, Mexico City.

Max B, Vibhakar S. Dolutegravir: a new HIV integrase inhibitor for the treatment of HIV infection. Future Virol 2014;9(11):967-978.

Mayer KH, Biello K, Novak DS, Krakower D, Mimiaga MJ. PrEP uptake disparities in a diverse on-line sample of men who have sex with men. CROI 2017; Abstr 971.

Mayer KH, Mimiaga MJ, Gelman M, et al. Raltegravir, tenofovir DF, and emtricitabine for postexposure prophylaxis to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV: Safety, tolerability, and adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;59:354-359.

McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomized trial. Lancet. 2016;387:53-60.

Misra K, Huang J, Daskalakis DC, Udeagu CC. Impact of PrEP on Drug Resistance and Acute HIV Infection, New York City, 2015-2017. CROI 2019. Abstr 107.

Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2237-2246.

Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL et al. Effects of Emtricitabine/tenofovir on Bone Mineral Density in HIV-Negative Persons in a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(4):572-80.

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute ART Drug Interactions. www.hivguidelines.org. Updated April 2019.

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute PEP for HIV Prevention. www.hivguidelines.org. Updated March 2019.

Non-Occupational Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (nPEP) Toolkit. AIDS Education & Training Center Program. January 2018.

NYSDOH. The Licensed Pharmacist’s Role in Initiating HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis: Overview and Frequently Asked Questions. December 2017.

Otten RA, Smith DK, Adams DR, et al. Efficacy of postexposure prophylaxis after intravaginal exposure of pig-tailed macaques to a human-derived retrovirus (human immunodeficiency virus type 2). J Virol 2000;74:9771-9775.

Owens DK. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection: US Preventative Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2203-13.

Parkin JM, Murphy M, Andersons J, et al. Tolerability and side-effects of post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. Lancet 2000;355:9205:722-3.

Pilcher CD, Tien HC, Eron JJ, et al. Brief but efficient: Acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis 2004;189:1785-1792.

Pinkerton SD, Martin JN, Roland ME, et al. Cost-effectiveness of postexposure prophylaxis after sexual or injection-drug exposure to human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:46-54.

Qato DM, Zenk S, Wilder J et al. The availability of pharmacies in the United States: 2007-2015. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183172.

Radzio-Basu J, Council O, Cong M, et al. Drug resistance emergence in macaques administered cabotegravir long-acting for pre-exposure prophylaxis during acute SHIV infection. Nat Commun. 2019;10.

Raltegravir package insert. Whitehouse Station, NJ. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2014-2019.

Raltegravir. AIDSInfo U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. November 2018.

Ray AS, Fordyce MW, Hitchcock MJ. Antiviral Res. 2016;125:63-70.

Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM et al. The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28(12)841-9.

Smith MS, Foresman L, Lopez GJ, et al. Lasting effects of transient postinoculation tenofovir [9-R-(2-Phosphonomethoxypropyl)adenine] treatment on SHIV (KU2) infection of rhesus macaques. Virology 2000;277:306-315.

Song I, Borland J, Arya N, et al. Pharmacokinetics of dolutegravir when administered with mineral supplements in healthy adult subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 2015;55(5):490-496.

Song I, Zong J, Borland J, et al. The effect of dolutegravir on the pharmacokinetics of metformin in healthy subjects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72(4):400-407.

Spinner CD, Brunetta J, Shalit P, et al. DISCOVER study for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): F/TAF has a more rapid onset and longer sustained duration of HIV protection compared with F/TDF. 10th IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2019), July 21-24, 2019, Mexico City. Abstract TUAC0403LB.

Tenofovir package insert. Foster City, CA. Gilead Sciences. Revised April 2019.

Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. AIDSInfo U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. April 2019.

Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423-434.

Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, et al. Association of HIV preexposure prophylaxis with incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals at high risk of HIV infection. JAMA. 2019; 213(14):1380-90.

Tung E, Thomas A, Eichner A, Shalit P. Feasibility of a pharmacist-run HIV PrEP clinic in a community pharmacy setting. Poster presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, February 13–16, 2017. Seattle, WA (Abstract 961).

Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411-422.

Van Rompay KK, Miller MD, Marthas ML, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic benefits of short-term 9-[2-(R)-(phosphonomethoxy) propyl]adenine (PMPA) administration to newborn macaques following oral inoculation with simian immunodeficiency virus with reduced susceptibility to PMPA. J Virol 2000;74:1767-1774.

Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis 2005;191:1403-1409.

Weiss K, Bratcher A, Sullivan PS, Siegler AJ. Geographic Access to PrEP Clinics Among US MSM: Documenting PrEP Deserts. CROI 2018; Abstr 1006.

World Health Organization. What’s the 2+1+1? Event-driven oral pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV for men who have sex with men: Update to WHO’s recommendation on oral PrEP. Geneva: 2019 (WHO/CDS/HIV/19.8). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Zash R, Holmes L, Makhema J, et al. Surveillance for neural tube defects following antiretroviral exposure from conception. Presented at: 22nd International AIDS Conference. 2018. Amsterdam, Netherlands. Available at: http://www.natap.org/2018/IAC/IAC_52.htm.

Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Neural-Tube Defects and Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:827-840.

Back to Top